Keep on Singing

When I lived in Paterson, New Jersey, I would walk around the neighborhood on Sunday afternoons and hear shouts of joy and songs of hope coming from storefront churches. At first, I would get uncomfortable. I didn’t trust the emotions that I heard. How can these folks be so joyful and hopeful amid all the poverty and pain around them? I thought their ecstasy was sheer escapism.

Then I heard Presiding Bishop Michael Curry talk about African American spirituality. “Why didn’t slaves go crazy?” Curry asked. “They had no doctors, no therapists, or social workers. Even families were separated and sold. I believe it was their singing. Spirituals took away their shame, wiped away their tears and made them part of God’s own family.” Their singing freed their spirits in the midst of captivity, fed their souls in spite of physical hunger, healed their wounds of abuse, sustained them in the wilderness of oppression, and even guided brave souls to freedom.

The heritage of praising God, the sacred memory of jubilation – even in the midst of oppression, pain and trial – has been passed down through the generations. Miriam sang after crossing the Red Sea, and Deborah sang after defeating her people’s enemy. David praised God in song and his son Solomon sang of love. Isaiah wrote songs of exultation, Jeremiah lamented in song, and Zechariah sang as he rejoiced. Hannah and Mary sang when they learned of their pregnancies. Paul and Silas sang in prison, and the voices of heavens sang a new song of the lamb before the throne of God.

We sing to celebrate. We sing to grieve. We sing as we work. We sing to pray. We sing as we hike. We sing to make the world smaller. We sing to drown out voices of hate. And sometimes, we sing to stay warm, awake and even alive.

Where would we be without singing? I don’t know. Emily says that when she sings, it is the only thing she can think about; for her, singing gives her head a vacation from her cares and worries.

I have always loved to sing, and I am told that I usually sing a little off-key but with lots of gusto. When I was in school, we had to go to daily morning chapel. We would all line up in the hallway by class and height where we would be inspected for appropriate skirt lengths, clean blazers, and polished saddle shoes. If any one of these items were not in order (especially the length of our skirts), we would be sent home to redress and marked tardy for school. Then, those who survived dress inspection, would process into chapel singing a variety of familiar hymns, our favorite being, "For All the Saints."

When it came time for graduation, our class selected this same hymn for the processional. And so, on June 12, 1972, twenty-nine girls marched down the aisle in long white dresses, carrying a dozen red roses with tears in our eyes singing at the top of our lungs: “O blest communion, fellowship divine! We feebly struggle, they in glory in shine; yet all are one in thee, for all are thine, Alleluia, alleluia!”[vi]

Whenever I hear this hymn, I think about my school days and laugh. There we were a bunch of kids singing about the saints. We didn't know anything about the saints, and we certainly didn't think we were saints, much less behave like saints, and yet, we were drawn to sing about them. Now, when I think back on those days, I realize that we were what novelist Anne Tyler phrased, "saints maybe."[vii] We were, each and every one of us, potential saints. And only time would tell what would become of us. My and I classmates grew up. We became doctors, lawyers, writers, accountants, teachers, artists, civic volunteers, and ministers. We grew up to wives, lovers, mothers, and yes, grown-up daughters.

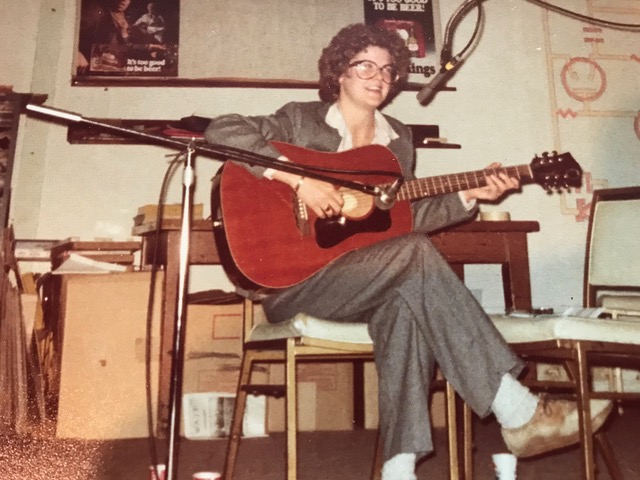

Singing has been an integral piece of my journey as a “saint maybe.” I have a song notebook (lyrics and guitar chords) in my own unique chronological order, and every song in my well-worn blue notebook reminds me of a particular phase, relationship or event in my life. On pages wrinkled with use and yellowed with age, there are lots of folk songs that I sang with my junior high friends in our band, The Checkerboard Squares: Wheat Checks, Rice Checks, Corn Checks, and Dog Chow (that was me). In the middle of the notebook, there are protest songs that I sang during my college years. Throughout the binder, you will find falling-in-love songs and breaking-up-is-hard-to-do songs (one or more for each relationship). There are the mountain songs and bluegrass melodies that I sang as I claimed my maternal roots. These are interspersed with the songs of the women’s movement that I learned during graduate school. And needless to say, there are songs for folk masses and youth groups, the music that brought me to the Episcopal Church in high school.

The Checker Board Squares - I’m “Dog Chow” without my guitar.

The most important songs in my notebook comprise what I call, My Coming Out Collection. This is the music that helped me claim the deepest, most intimate, and maybe the most complicated aspect of my life – my sexuality. One might say that I came out to music.

Now, I’m singing to keep my brain alive. We’ve all read how music and memory go together. I’m playing and listening music daily. Music is so important to my spirit that I’m making a playlist for when I can’t remember the songs I love including: childhood lullabies, high school favorites, falling in and out of love songs, protest songs, mountain songs, coming of age songs, coming out songs, hymns, road music, yoga favorites, and the great classics of the baroque, rock ‘n roll, motown, and bluegrass.

A long time ago, I made a promise to God and myself: no matter what happens, come hell or high water, no storm will shake my inmost calm, for I’m gonna keep on singing, all the days of my life. - Tracey

Parts of this blog were excerpted from my book Interrupted by God: Glimpses from the Edge.