Speaking Out

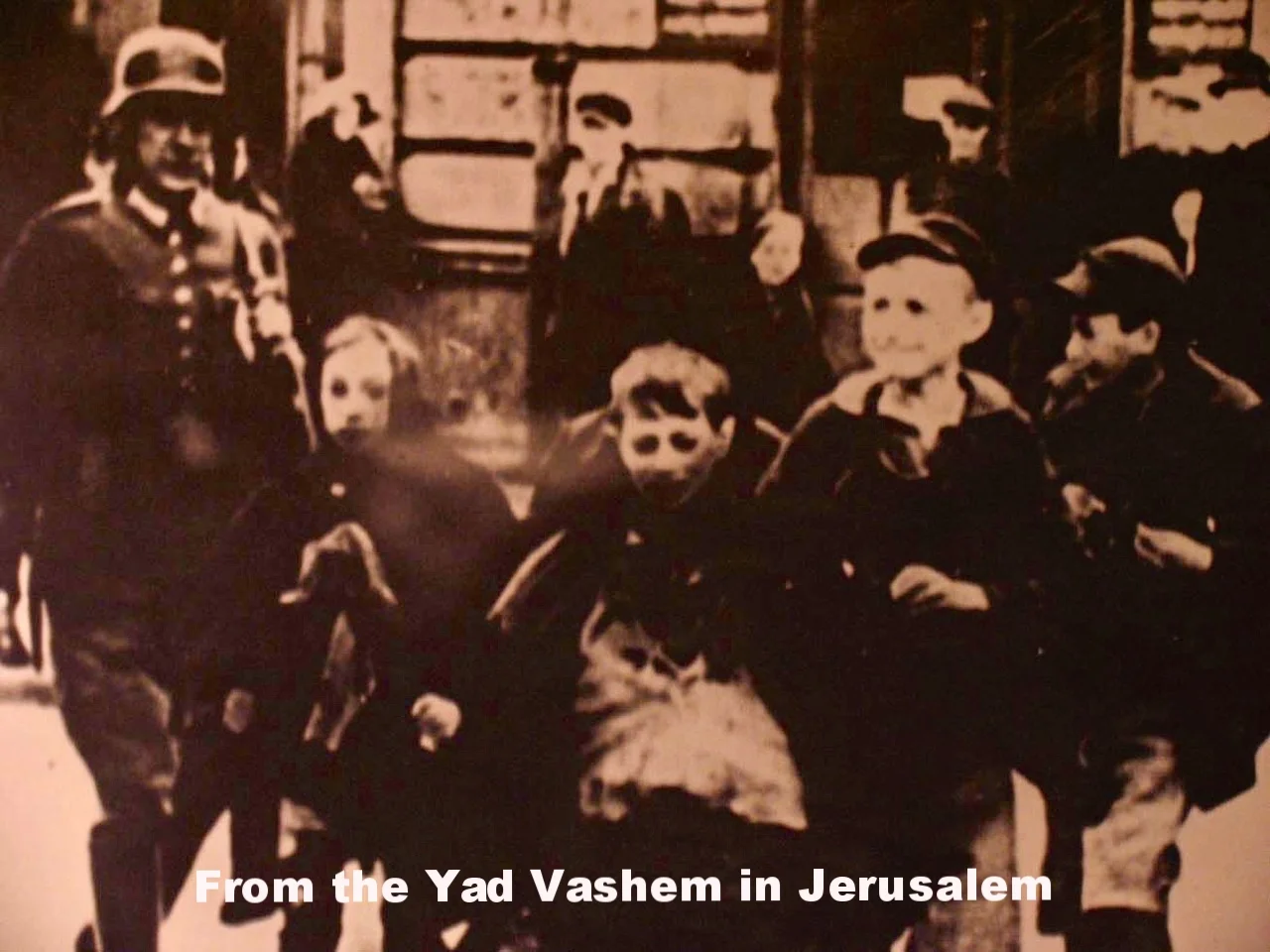

A half century ago, I sat in a classroom with a group of adolescents watching the film “Let My People Go,” a documentary about the Holocaust. I’ll always be haunted by the memory of emaciated corpses being pushed down a slide in the Warsaw Ghetto. At the end of the film, a young rabbi tried to elicit responses from a stunned and silent class of usually loud and obnoxious ninth-graders. I’ll never forget the moment when he looked at me, the only kid with a non-Jewish parent, and said, “Tracey, you don’t look Jewish. You could have passed. What would you have done?”

That accusatory statement, “You could have passed,” followed by the probing question, “What would you have done,” has haunted me all the days of my life. And just when I think I have put the accusation to rest and answered the question, it re-emerges as a beast from the deep recesses of my unconscious.

To pass has many implications. Passing can be as simple and as seemingly innocent as allowing a racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, or homophobic remark to go unnoticed. It can mean worshipping a homeless man on Sunday and walking by without seeing dozens of homeless men, women and children during the rest of the week. Passing can cause one to hide in all kinds of closets for all kinds of reasons. Passing can mean taking the easy way out, even at the cost of one’s soul. And now I’m learning that passing can simply mean doing and saying nothing as the world spins.

One of the common symptoms of FTD (Frontotemporal Degeneration) is inertia and apathy. These days, I lack the motivation, spontaneity and get-up-and-go energy that I used to exhibit, the kind of energy that community organizing and witness in the public square demand.

As I am unsure of my cognitive abilities, I’m afraid to speak out about what’s going on in our nation and world. I’m worried that I might say something inappropriate, not have my facts straight or be unable to handle the attacks that come from raising my voice.

And, since large crowds make me nervous, I tend to avoid public actions, marches and demonstrations. When it comes to standing up against the emerging policies and actions of our current presidential administration, legislature, and supreme court, especially on issues such as immigration, gun violence, the environment, healthcare, the economy, and foreign relations, I’ve taken a pass and become an armchair activist.

This past Sunday’s Hebrew Scripture passage tells us that, “God does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but God looks on the heart.”(1 Samuel 16:7). In the Gospel, Jesus compares God’s commonwealth to like a mustard seed (Mark 4:31), starting out as small and fragile but growing into a disruptive and disorderly weed that produces protective shade in which vulnerable birds and their precious cargo can safely nest.

Sitting on our front porch — where three different mother birds have nested in our hanging ferns — meditating on scripture, saying my prayers, reading newspapers, watching television talk shows, and scanning Facebook and Twitter — I realize that I can’t keep silent; I can’t take a pass. As we approach Independence Day, all of us need to speak out about the policies and actions of our nation’s government.

What’s happening in our country frightens me. As a student of history, I’m seeing too many comparisons with previous fascist regimes, especially the Roman Empire and the Third Reich. In my mind, the often repeated words of Martin Niemöller, inscribed on the wall of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in our nation’s capital, are taking on new and more urgent significance.

“First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Like many Protestant clergy in Germany, Niemöller was a conservative Lutheran pastor who initially supported Adolf Hitler’s ascent into political power. However, in 1934, coming to see the growing abuses and hatred perpetrated by the Third Reich, Niemöller joined with other Christian clergy to form the Confessing Church and to criticize Nazi policies and practices as incompatible with Christian values. Along with other resisters, Niemöller was arrested and sent to a concentration camp.

They are coming for black and brown people. They are coming for immigrant people. They are coming for queer people. They are coming for poor people. They are coming for sick people. They are coming for oppressed people, including the most vulnerable among us — undocumented migrant children.

Drawn by a Palestinian child

As a person with dementia, I am worried. I no longer qualify for certain kinds of insurance because I now have a pre-existing condition. What if our financial resources aren’t sufficient to provide for my care as my disease progresses? Will my spouse be forced to spend every last dime on my care, leaving herself impoverished; or, will I eventually be perceived as a burden on society and warehoused in some government facility? Even if I can afford quality care, will my advance directives be honored and my end-of-life decisions be respected by a government whose policies and judicial decisions are becoming more rigid and less compassionate? Will they come for me, and there will be no one left to speak up?

In 1973, William Stringfellow, lawyer, political activist, and devoted Episcopalian, published an essay entitled “Living Humanly in the Midst of Death” in the book An Ethic for Christians & Other Aliens in a Strange Land. Examining why people like Niemöller spoke out in resistance to the Third Reich, Stringfellow wrote, “To exist under Nazism in silence, conformity, fear, acquiescence [and] collaboration – to covet ‘safety’ or ‘security’ on the conditions prescribed by the state – caused moral insanity, meant suicide, was fatally dehumanizing, [and] constituted a form of death. Resistance was the only stance worthy of a human being, as much in responsibility to oneself as to all other humans, as the famous commandment mentions.”

Stringfellow argued that while resisting oppression ensured risk and peril, nonresistance or acquiescence “involved the certitude of death – of moral death, of the death to one’s humanity, of the death to sanity and conscience, of the death that possesses humans profoundly ungrateful for their own lives and for the lives of others…”

I think we would be well advised to heed the words of both Stringfellow and Niemöller, and speak out while we still have the freedom to do so. Otherwise, as hard as it is to imagine, there might come a time when exercising our freedom of speech might become a risky and dangerous act. And, if we are silent for too long, there might not be anybody left to speak for you and me. - Tracey

________________________________________________________________________

“Living Humanly in the Midst of Death,” A Keeper of the Word: Selected Writings of William Stringfellow, edited by Bill Wylie Kellerman (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994) 345