Embracing Comfort in a World of Yoga Pants

My favorite exercise outfit. Sexy? No. Comfortable? Yes!

Last week, I read a New York Times Op-Ed, Why Yoga Pants are Bad for Women. On behalf of many middle age women, Honor Jones makes the argument that we don’t need to look sexy in yoga pants in order to get fit. I couldn’t agree with her more.

If you’ve been following my blog and Facebook posts, you know I’m trying to be intentional about self-care. I’m eating healthy, walking every day, swimming a few times a week, bike riding as much as I can, doing memory exercises, and practicing yoga and meditation. It’s not easy; and for me, it requires a lot of time and discipline. However, I know it’s good for my brain, body, and spirit.

It’s hard enough being less balanced and flexible than everyone else in my yoga class; it’s hard enough giving up wheat and sugar; and it’s hard enough getting my 12,000 steps and 1 hour of aerobic exercise a day. But to worry about how I look while I’m doing it – that’s really unfair and too much to ask.

I agree with Honor Jones – yoga pants and tops are for the birds or women who eat like a bird. I hate spending half of my class or exercise time adjusting my clothes, pulling up on my bottoms and down on my tops. Unless you’re in great shape (both top and bottom), yoga pants and tops (you simply can’t call them shirts) are not attractive; in fact, they emphasize all the wrong aspects on a middle-aged body. And, to add insult to injury, they are overpriced.

Recently, I heard a funny song by Micah Tyler, “You’ve Gotta Love Millennials,” where he jokes about young women changing the world while wearing yoga pants. Last week, I realized that I’ve handed over the torch of trying to change the world to my millennial friends. So, I don’t have to wear yoga pants. I also don’t have to wear business suits and high heels. In an effort to mark this transition, and to simplify my wardrobe, I packed up bags of professional clothing and donated it to Dress for Success, a wonderful organization that helps women enter and/or re-enter the workforce. I also packed up a bag of casual clothing that I had intended to take to a local thrift store. After reading Honor Jones’ Op-Ed, I opened the bag and pulled out my old sweat pants and a favorite T-shirt, put them on, and went to a yoga class. I might not have looked sexy, but I'm becoming more and more comfortable striking a pose on my mat of humility. - Tracey

Standing in Shifting Sands

Excerpts from a Sermon preached on the First Sunday of Lent

Coral Gables Congregational Church - Coral Gables, Florida

February 18, 2018

Mark 1:9-15

No Common Ground - Cleveland Republican National Convention 2016

While this morning I had intended to preach about living in the wilderness of dementia, the sands shifted when 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz walked into his old high school with an assault rifle and opened fire, deliberately killing seventeen people and wounding another fifteen. I can’t ignore this local tragedy or allow the national epidemic of gun violence to be buried in the sand.

I come from Ohio, a state that sends many snow birds to Florida each year, and like Florida, is a presidential swing state. Ohio is also a state, like Florida, with a strong gun lobby and lax gun laws. And, Ohio, like Florida, has experienced multiple, tragic, mass shootings.

Do you remember the Chardon, Ohio High School shooting in February, 2012? Probably not. We have become numb to these shootings. We see the news reports, the media covers it for a few days, and there are passionate statements about how we can never let it happen again. And then, we move on.

Unfortunately, the reality of gun violence in our nation is only getting worse. Since 2013, there have been nearly 300 school shootings in America — an average of about one a week. And, while more individuals in America are killed by guns than in car accidents, in many states (including Ohio and Florida), it's easier to buy a gun than to get a driver’s license. As we once again learned this past week, no matter where we live, work, play, pray, or go to school, a shooting can happen to someone we know or love, even to ourselves.

Gun violence is something we all have in common, and most Americans are concerned about it. However, there appears to be very little common ground in our attitudes about gun legislation. Two distinct cultures and worldviews are pitted against one another: gun control vs. the second amendment. And unfortunately, the latter seems to be winning with tremendous dollars being spent on advertising, lobbying and campaign contributions, especially in states like Florida and Ohio.

So, if we live in a nation with two distinct cultures and worldviews about guns, what are we to do? Some believe that gun legislation in this country is a hopeless cause. I’m here to tell you that nothing is hopeless – not gun violence and not dementia – for with God all things are possible.

On Election Day 2016, when I was diagnosed with a rare form of dementia called Frontotemporal Degeneration, life was turned upside down like an hour glass as we learned that I had a brain disease that we never knew existed. Like Jesus in the afterglow of his baptism, we wandered out of the doctor’s office into the wilderness of dementia, and discernment. We had to accept the reality of my condition and discern what would become of us.

Shortly after I retired, we went on a journey – not 40 days and 40 nights in the desert – but 14 days at sea. As we passed through the Straits of Gibraltar under the full moon of Holy Week, something inside of me shifted… I decided that instead of drowning in what I had perceived to be quick sand, I wanted to ride the shifting sands of my life, and Emily decided to start mapping our course for the journey. We’re now walking in this uncharted and sometimes frightening wilderness, discovering a new fullness of life.

Mark’s gospel tells us that while Jesus sojourned in the wilderness, he was tempted by Satan – not necessarily the devil or the evil one, but quite possibly, the agent of God who was given the task of testing the fidelity and righteousness of humanity, the same biblical character in the Hebrew Bible who tested Job. Over the past year, I have confronted the great tester as well – tempted to deny the reality of my disease, to believe I can return to my former life, and to assume that I can’t slow or even reverse the deterioration of my brain…

I think the tempter is testing our nation when it comes to gun violence. We can’t return to the way life was in previous generations; to do so is to live in a golden age of memory (which by the way, wasn’t all that golden for everybody). Rather, we have to find a way forward in the wilderness of the 21st century, offering hope, safety, and help to one another.

I do not believe we are going to eliminate guns in America, so we need to figure out how to coexist with them. As New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof has suggested, we need is a public health approach to gun legislation similar to the model we use to reduce deaths from other potentially dangerous things around us, such as swimming pools, cigarettes, alcohol, and automobiles.

Jesus’ time in the wilderness has something to teach us about co-existing with things that make us afraid. According to the text, Jesus was not alone in the desert. The oldest gospel account tells us that he was with wild beasts. Christian tradition has assumed those beasts to be threatening enemies, dangerous bedfellows, aggravating predators, or at best, bothersome nuisances – a theological perspective consistent with the understanding of nature as something to be conquered and subdued. Consciously or unconsciously, this perspective also has informed gun legislation in America; there is danger lurking on every corner, so we had better defend ourselves with guns.

Perhaps however, the wild beasts were not foes, but rather, Jesus’ companions in the wilderness. They might have summoned the angels to minister to Jesus; or maybe, they were the angels, teaching and helping him survive his time in the desert.

I have met some interesting folks on my journey through the shifting sands of life, who at first, seemed threatening, but over time, became companions, friends and teachers. I’ve also been the beneficiary of extraordinary kindness, generous hospitality and amazing gifts from angels in all sorts of disguises, including those with whom I’ve had political differences of opinion on various topics, such as gun control.

Through our journey in a new wilderness, Emily and I have experienced first-hand how hugely important welcome, inclusion, acceptance, compassion, and advocacy are, especially to strangers, sojourners, newcomers and misfits. While less than 5% of shootings are committed by those with diagnosable mental illness, who knows how much gun violence could be eliminated if those struggling with mental and emotional illness and other cognitive disorders were truly welcomed and cared for in our communities.

I have been told that you have you have joined congregations across the country in efforts to reduce gun violence and to reduce the stigma and promote the inclusion of individuals and families living with dementia and mental illness in the life of the faith community.

This is really important ministry, for as we have once again witnessed in this week’s tragic school shooting, our nation needs to both eliminate gun violence, to separately address the growing issues of mental illness, dementia and brain disorders in our country, and to not conflate the two. Along with working for responsible gun legislation and supporting families affected by gun violence, providing welcome, support and advocacy for people who are living with brain diseases of all sorts is a way the church can step into the complicated fray called life the 21st century.

In order to carry out your two-prong ministry, you will need to learn about gun violence, the gun lobby, and gun legislation in America, and develop an intentional practice of really seeing, knowing, understanding, appreciating and including people with cognitive and emotional challenges. Both of these are commitments that will require you to come close to your own fears. In doing so, you might be tempted to run away. I know I have been, but don’t. Stay in the wilderness and call upon both the beasts and the angels into ministry so that you might be become a beacon of hope to this broken, wounded, frightened and divided nation.

[1] Everytownresearch.org

[2] (NYT, 10/3/15)

[3] Gun Violence and Mental Illness, edited by Liza Gold and Robert Simon, 2016

Finding Hope in Pandora's Box

Hope - Amelia Island, Florida

I’m writing from Coral Gables Congregational Church in Florida, where I’ll preach this coming Sunday. Emily and I are leading a Saturday retreat for individuals and care partners living with early to mid-stage dementia. It’s beautiful outside: sunny, warm and humid. We’re staying in the church’s guest house, just down the block from the Biltmore Hotel. You should see the pool.

My internal clock is a bit off as I was in San Francisco last week to speak at Church Divinity School of the Pacific (one of the Episcopal Church’s denominational seminaries) and the Sequoias at Portola Valley, a lovely retirement community in the rolling hills of the Bay Area.

Traveling and speaking this way has been both a dream come true and a surreal experience. In some ways, I feel like I’ve opened up Pandora’s Box. When I tell my story, all kinds of people (young and old) start sharing their experiences. That shouldn’t be surprising, as one in four people over the age of 85 and one in ten over the age of 65 have some form of dementia.

Someone suggested that I might not want to use the metaphor of Pandora’s Box since the word implies “bad stuff happening to good people.” In case you don’t remember the myth, it goes like this:

Once upon a time, there were two brother gods named Epimetheus and Prometheus. One day, Prometheus discovered the secret of fire, and this angered Zeus. As punishment, Zeus chained Prometheus to a rock for many years. And if that wasn’t enough, the great god went after Epimetheus by way of a trick. First, Zeus ordered Hephaestus, the maker of all things, to craft him a daughter out of clay. Zeus named her Pandora, brought her to life, and gave her as a bride to Epimetheus. Zeus then gave the newlywed couple a gift – a locked box (perhaps, it was a jar) with a note that said, “Do not open.” Attached to the note was a key.

Of course, you know what happened next. Pandora’s curiosity got the better of her, and she took the key and opened the box (or jar). When she raised the lid, lots of bad things – envy, sickness, hatred, disease, war, pestilence, famine – flew out into the world. By the time Pandora closed the lid, it was too late. The world was no longer perfect.

Epimetheus heard Pandora crying and came running. She opened the lid to show him that the box (or jar) was empty. When she did, one little bug flew out, smiled, and flew away. That little bug was named HOPE. And that little bug made all the difference, giving hope to people that we could make the world a better place to live, in spite of the bad stuff. And by the way, Zeus’ heart was softened, and he freed Prometheus.

So, in speaking openly about dementia, I feel like I’ve opened Pandora’s Box because I’m talking about something that we all dread, but I’m also offering hope that we can discover the fullness of life in spite of (or perhaps because of) dementia. I’ve also come to realize, like with Pandora’s box, there’s “no going back" to the way life used to be, now that I’ve publicly acknowledged that I’m dealing with Frontotemporal Degeneration. I’ve closed some doors and opened others. My challenges and limitations can’t be kept secret any more, which is why so many people refuse to recognize cognitive problems and seek help.

I’m hopeful that someday there will be a cure for this disease. I’m also hopeful that I and others living with dementia can improve the quality of our lives – our bodies, minds and spirits – by being honest, transparent, and willing to make some changes in the way we live. I’m hopeful that by acknowledging the reality of dementia, this much-dreaded and feared disease will be a stop along the way of our human journey and not the final end of the script.

How's Emily?

Wherever Tracey goes, people keep asking her how I am doing. I’m fine. Except when I’m not.

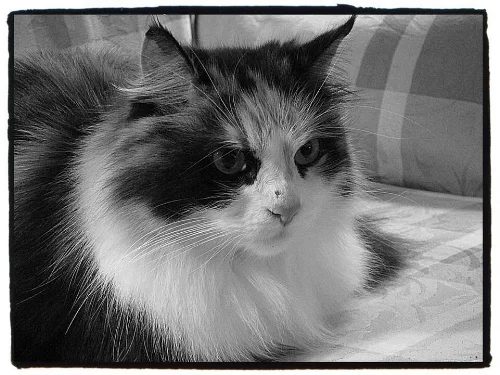

My cat died. My beautiful Delilah died. While I admit that over the years more than one friend has told me that she would like to die and be reincarnated as one of my cats, I am not a Cat Lady. I have nearly always had a cat in the house, but usually just one. For the past twelve years there have been two, Samson and Delilah. (You knew that was coming, didn’t you?)

They are not my children, they are cats. And yet ...

One day she was there, that gorgeous little fur ball, occasional pain in the ass, kissy, pestiferous, whimsical animal … then not there. Tracey and I held her to the end and even after she was dead, she was still so soft and warm that I couldn’t take it in. I was devastated. Later that night as I started to fall asleep I reached out to where she always used to curl up next to me and she wasn’t there. I fell apart and just sobbed. And sobbed. And sobbed.

So, OK. I do know it wasn’t just the cat.

I also wept for my mother, who died last year at this time. I wept for my life turned upside down and my relationship indelibly changed by a disease that I did not even know existed 18 months ago. I wept for all the losses of the past year: my cozy, independent, homebody life; my house and my garden and my family that I miss when we travel so much; my church community that anchored me; my faith that anything in this world makes any sense at all; and I wept in that anticipatory grief well known to people facing the long goodbye of a loved one with dementia. And for the cat, too.

“Grief is a lonesome valley and we each have to walk it in our own way.”

Beautiful Delilah, 3/23/2006 — 1/25/2018

But the story is not all about grief. Of course I felt better after I cried it all out, and then I began to think about how the losses of the past year have also offered amazing gifts. Our new nomadic life is rich and full. We have traveled to beautiful, interesting places and along the way we have shed a lot of baggage, emotional and physical, so we travel more lightly. We have made new friendships and deepened old ones. I have copious notes and photos of gardens that I want to replicate in my own backyard someday but it’s OK that someday is not now. Time is more precious, but also more generous. Our relationship has grown much stronger and deeper. And the ones who have gone before us have left behind their beauty and laughter and life lessons that will always be with us.

I will plant Delilah’s ashes under a bush near the bird feeder. She was fond of birds. And later this spring my family will go to Buffalo and we will plant my mother’s ashes under an oak tree in the family cemetery. In both places I expect I will shed some tears and also smile when I think about the gifts they gave me and the stories I will tell them when I get to the other side of the valley.

How am I? I’m well. Thanks for asking. — Emily

The Mat of Humility

My yoga studio's room with a view

I’m still learning the spiritual lessons of humility the hard way. Honestly, everyday seems to reinforce the teaching. Last week was no exception.

I went to a morning yoga class at “my studio,” Vision Yoga and Wellness, where I am twice the age of my teacher and most of my classmates. I’m not nearly as limber, flexible, balanced or strong as they are, but for the past two years, I’ve been giving it my best effort. Yesterday’s class was particularly challenging because it required lots of deep knee bends and one-leg stands, neither of which I do very well any more. I spent much of the hour modifying poses while feeling frustrated and humiliated, especially when I found myself facing the opposite direction from the rest of the class. I know that each of us has our own practice, and everyone is called to pay attention to one’s own mat. But really…

At one point, as everybody else was working on some complex posture, I finally gave into my body’s limitations and rested in child’s pose – knees bent, forehead to the ground, and arms stretched out in front. Listening to my breath, I was reminded of the beggars in Paris who assume this same posture in front of the expensive stores on the Champs-Élysées.

Then, I began to think about the act of prostration, an ancient prayer position. You can witness this pose in cathedrals, churches, monasteries and convents, especially at an ordination to the priesthood or the taking of final monastic vows. You see it in West Africa when someone visits the shrine of a deity. You see it in a mosque with men and women at prayer. In yoga, child’s pose is considered an “active” resting posture. For me, it’s often a moment of prayer, a time of re-centering and reminding myself that the universe is a big place, and I’m one small participant in its grand story. Any way you look at it, getting down on your knees or flat on your stomach, placing your hands in front of your body on the ground, and lowering your head until your forehead touches the ground is a humbling action.

In my child’s pose, as I prayed for acceptance, grace, and the ability to get back up, I was reminded of just how hard it is for me to be humble, and how humbling it is to have early stage dementia. Isn’t there an easier way to learn the lessons of life?