The Truth Will Set Us Free

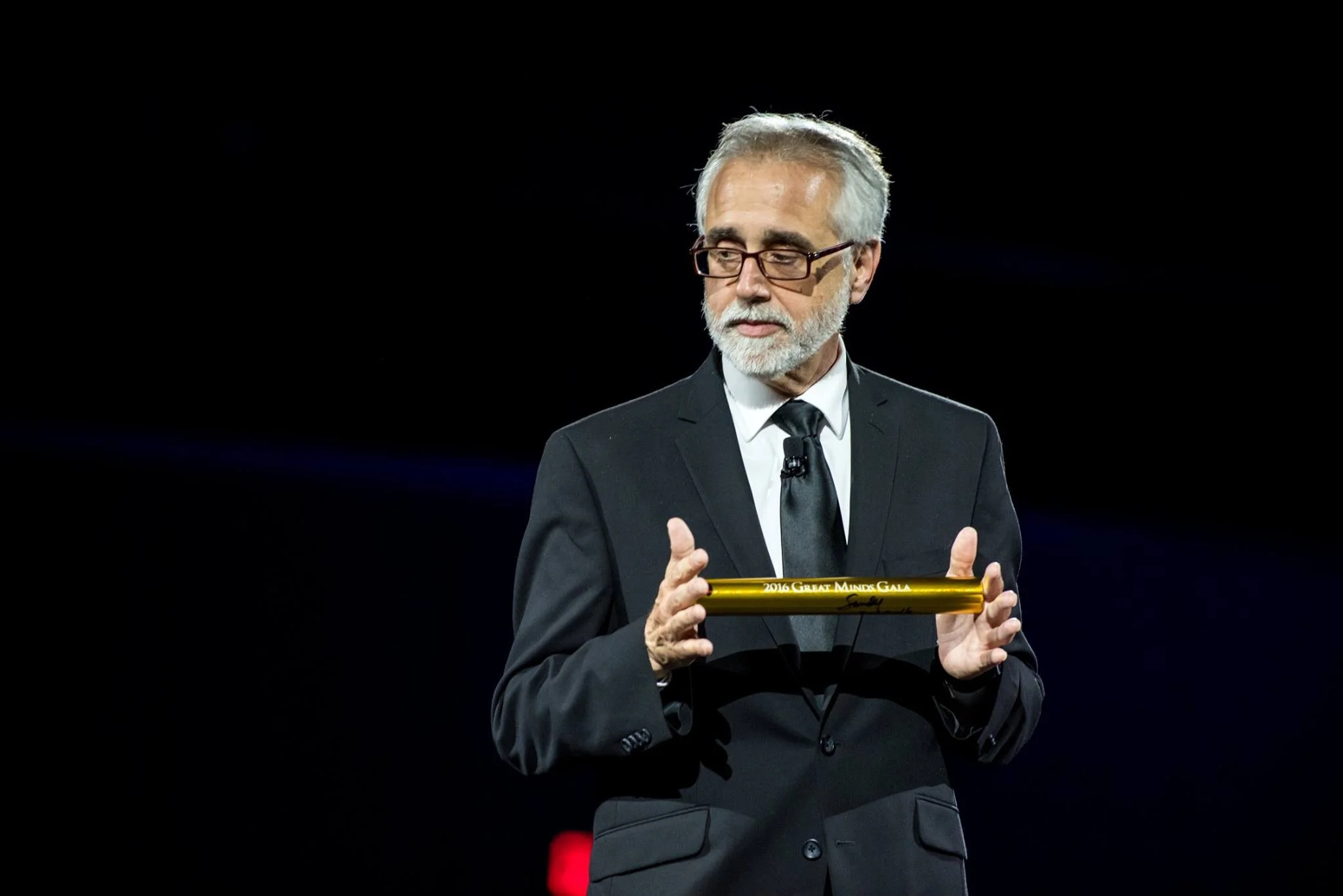

Speaking at the Great Minds Gala, Leading Age PEAK Conference

Denial is a fairly common reaction to upsetting news. Do we believe the child who whispers the pain of abuse, the teenager who reports bullying, the employee who brings charges of harassment, or the immigrant who pleads for refugee status? We often miss the truth because we can’t or won’t believe the messenger or the message.

People sometimes say to me, “You don’t seem like you have dementia.” But what does this mean? Ah yes, someone with dementia is wandering around a memory unit with cookie crumbs on her shirt, wearing adult diapers, holding a stuffed animal, staring into space, and maybe babbling or moaning. No, that’s not me; nor is it any of the other folks I’ve met over that past year who are in the early to mid-stages of this disease.

Some days, I feel like my old self and question the diagnosis. But then something will happen - like getting disoriented at a crowded party, frightened in an airport, startled on a busy sidewalk, struggling to find words or make sentences, having an outburst in public, or being overwhelmed by the number of clothing options in my closet and meal choices on a menu. These moments remind me that yes, I do have dementia. Some of my friends on the FTD Facebook support group call it having an “FTD day.” One of my new friends with early onset Alzheimer’s says there are days when he gets “bit in the butt” by dementia.

I’ve learned denial is a common challenge, especially for those with early onset (diagnosed before age 65). Because it’s such a devastating diagnosis, friends and strangers want to offer comfort by saying things like, “Oh, we all forget where we placed our keys, and we all get confused. Sometimes I can’t recall my best friend’s name or the day of the week.”

These days, I’m fairly direct about letting the well-intended know that it’s neither comforting nor helpful to tell someone that their reality seems to be “an idle tale.” In fact, it’s one of the most difficult parts of coping with this illness, and it can lead to an unhealthy cycle of denial, shame or blame.

Many individuals with dementia are not sitting in chairs, lost in space. Instead, we’re living our lives to the best of our ability as we try to destigmatize this dreaded and misunderstood condition, believing that if we are honest about our reality, the truth will set us free to explore the fullness of life with it.

So today, I want to salute all of my sisters and brothers living with dementia, especially those who are out in the world speaking, teaching and advocating through organizations like The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, FrontoTemporal Dementia Advocacy Resource Network, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the Dementia Action Alliance. I’ve met some amazing individuals through these organizations; they are my role models and mentors, and I am grateful for their friendship, leadership and witness.

And to my friends and supporters who don’t have dementia: Please, don’t deny my truth. Instead, tell me that you’re happy to see me; that you’re glad I’m doing well; and that you will forgive me if I can’t remember your name or recognize your face.

Pictured above: A panel of dementia advocates at the Leading Age PEAK conference, Brian LeBlanc, dementia advocate, Brian Van Buren, dementia advocate.

Did You Miss Easter?

The Road to Emmaus - Holy Land 2004

Did you miss Easter? It happens all the time. Lots of people miss Easter. Even well-intended, faithful people miss Easter. As my old friend Sam Portaro once wrote: “If you missed Easter, you're in good company; history’s on your side.” (1)

According to the gospel accounts, very few people were actually around for the first Easter. Sure, there were curiosity seekers who watched, and maybe even followed along, as Jesus carried his cross through Jerusalem. There was a small group of loyal women, including Jesus' mother and Mary Magdalene. There were Roman guards, and perhaps, a few religious and political authorities keeping an eye on the execution. There was also a scattering of onlookers at Golgotha.

There were a couple of folks who took Jesus' dead body off the cross and carried it to the tomb. And on that first Easter morning, depending on whose gospel record you're reading, Mary Magdalene, a few other women, and Peter went to the empty tomb. Luke's gospel then records an episode on the road to Emmaus with two other disciples, as well as a meal with the rest of them; and Matthew tells of the Risen Lord meeting the twelve disciples (less Judas) on the mountain, ordering them to make more disciples, to baptize and teach in his name.

And then there's John's Gospel account. It tells us that Nicodemus, who had first come to Jesus in the night, helped Joseph of Arimathea prepare Jesus' body for burial and carry him to the tomb. It recalls Mary Magdalene visiting the tomb while it was still dark, finding the stone rolled away and running for Simon Peter and the other disciple whom Jesus loved. The Fourth Gospel also recounts several post-Easter appearances of the Risen Christ, including two visitations to the disciples in an Upper Room; Thomas’ demand to see and touch Jesus’ wounds; Jesus cooking breakfast on the beach and instructing the disciples on where to drop their fish nets for a miraculous catch; and lastly, Jesus' conversation with Peter about love and loyalty.

It’s not because they went to Easter, but rather because Easter came to them. Easter came to Mary, who thought he was a gardener. Easter came to Thomas and others locked away in fear. Easter came to pilgrims on the road to Emmaus, and to disciples fishing in the early morning hours. Easter finally came to Simon Peter in a moment of repentance and reconciliation.

Light of the World - Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem, 2004

Easter comes to us, and not always on Easter Sunday. Often, maybe usually, Easter comes to us when and where we least expect it. I’ve witnessed Easter come to hospital rooms, homeless shelters, and unemployment lines. I’ve seen Easter show up at a crowded restaurant, a city sidewalk and a lonely beach. And yes, Easter can come to someone sitting in church but not expecting to receive the good news of resurrection.

Last year, Easter came to me in a most unexpected way when I was newly diagnosed with dementia and spent Holy Week on a transatlantic, repositioning cruise, passing through the Strait of Gibraltar under the full moon of Maundy Thursday. Since then, I’ve been traveling the globe and living in the realm of God in some new and wonderful ways, discovering and claiming the fullness of a life with dementia.

Resurrection - the central message of Easter, a stumbling block for many - is a paradigm shift: an altering, breaking, and transforming of the rules. It changes the most powerful and pervasive rules of all - that good guys finish last, evil wins, and death has the final word. Resurrection says that, in God’s realm, good guys and gals finish first. Resurrection insists that goodness can overcome evil. Resurrection also says no to the finality of the grave, and yes to life. Yet, paradigm shifts - especially those that are profound and life changing - are hard to explain and harder to accept, even for those who see with their own eyes and touch with their own hands.

Thomas Kuhn, in his groundbreaking book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, explained the power of paradigms this way. If I show you a deck of cards, you know what to expect. The red cards are diamonds and hearts, and the black cards are clubs and spades. But what if I show you a red spade? Experiments have demonstrated that chances are fairly certain your eye won't see it. Rather, you will most likely insist that my spade is in fact a heart or diamond. Why? Because that's just the way things are.

The resistance to paradigm shifts is as old as history itself. Remember Galileo, the one who insisted that the earth revolved around the sun, and not the other way around. He was excommunicated because of his wild, heretical ideas. Or Peter Abelard, who taught that God’s love was universal and unconditional; he too was excommunicated. Simply put, Jesus was all about shifting paradigms, and the resurrection was the biggest shift of all.

Thomas, whom tradition calls The Doubter, wasn't with the disciples the first time the Risen Christ visited them in the Upper Room. While they were locked inside for fear, Thomas was out in the world. Maybe he was out buying groceries. Maybe he was going stir-crazy and had to get some fresh air. Who knows? But he wasn't there the first time Easter came around. And when he returned, he demanded proof: "I'm not going to believe this miracle unless I see it for myself."

As Frederick Buechner writes: “Imagination was not Thomas’ long suit...He was a realist. He didn’t believe in fairy tales, and if anything else came up that he didn’t believe in or couldn’t understand, his questions could be pretty direct.” (2)

You know what that's like. Your friends, family or co-workers tell you about an event that sounds too good to be true, and deep down inside, you don't believe it. It happens to me all the time. Someone tells me about a fabulous movie, a great restaurant, a book that I must read, or an easy diet or a simple exercise routine that promises miraculous results. I listen intently, and then I think to myself: maybe, we'll see. And then if I check it out for myself, I discover that sometimes they’re right, and sometimes, they’re not.

Thomas saw, heard, and touched. Jesus showed up again, just for his sake. Easter came to Thomas in a most unexpected way, and yet, it was exactly what he asked for.

Spring is coming - Kew Gardens, London, 2007

With all of our uncertainty and doubt, you and I approach the empty tomb, the wounds of the Risen Christ, and the mystery of resurrection in differing ways. But in showing up, in being present and accounted for, in acknowledging our uncertainties, and in asking God to accept both our faith and our doubt, Jesus replies, "Blessed are [you] who come to believe" - however you get there.

So, if you missed Easter, it’s all right. If you open your eyes, ears, mind and spirit, Easter will come and find you, wherever you are. But it doesn’t hurt to ask for a little help. So why not give it chance. Ask to meet the Risen Christ, and be ready to welcome Easter into your life. - Tracey

1 - Sam Portaro, “Missing Easter,” http://credoveni.wordpress.com/2012/04/08

2 - Frederick Buechner, Peculiar Treasures: A Biblical Who’s Who, New York, Harper & Row, 1979, 165.

Mindfulness, My Way

Tracey and I are visiting friends and getting some R&R in California this week. Yesterday in Mountain View, we went into a bookstore that got me thinking about mindfulness.

Tracey was looking for a copy of James Carroll’s new novel, The Cloister, and she asked the proprietor whether he carried it.

“Is it a spiritual book?” he asked. “This is a spiritual bookstore.”

We looked around, and there were books on all sorts of topics: wisdom ancient and modern — Buddha, Swami Kriyananda, yoga, feng shui, alternative healing, healthy diet, tarot and zen. There also were spirit rocks, crystals and scented candles with names like “Awareness” and “Inner Strength.”

This led to a lively discussion and some eye rolling later over lunch about why a novel written by a theologian in which the characters, including Abelard and Héloïse, struggle to work out their faith in a terrible world, would not count as “spiritual.” But that is for another day.

In the San Francisco Bay area, a lot of attention and commerce is paid to spirituality. Obviously, lots of people are looking for a path that taps into the essence of creation, that thing that explains it all, that well of understanding we call by many names and come to by many paths. I call it God, and I completely respect the names and paths followed by others. However we get there, it would be nice (and the world would be a better place) if we all would get there.

As I looked around the shelves, Dan Harris’ book, Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics, caught my eye. I laughed aloud. Now that’s a title for me! I am pretty good at sitting still when I have to. And I can focus on all sorts of things when I have to. But I am not good at paying attention, at being in the moment, being mindful. My mind wanders off in all directions, and I wonder whether it’s worth the effort to bring it back. Do I really want to be all that self-aware? What if I sit down, get all comfy on that cushion (in spite of my aching knees), tune in, open up and meet … myself? What if I don’t like the self I meet? Wouldn’t it be better to just go to the grocery store and accomplish at least one thing on my long to-do list?

Plenty of research clearly ties happiness and good health to nutrition, sleep, exercise, strong community and meditation. And this is a time in my life when I am relearning the importance of all of those things. Meditation in particular can calm stress, lower blood pressure, alleviate depression and increase awareness. The thing is, I have never had much temperament or interest in cultivating a practice of meditation, and so I can’t rely upon it when needed. Which is now. A little mindfulness and some inner tools for stress relief would go a long way as we bounce all over the world in and out of airports, train stations, churches and large conferences with keynote speeches. I am nearly as introverted as Tracey is extroverted, and although my parents trained me well, I really do best in smaller, quieter gatherings. A meditation practice probably would be helpful right now. I almost bought the book but decided on The Inner Life of Cats instead.

Yesterday afternoon, we drove along the coast to Bean Hollow State Beach and climbed around on the rocks at low tide. I stood next to the ocean looking at whale spouts far out to sea. Then, my eyes returned to the sand beneath my feet, the anemones tucked among the rocks on which I perched, the tidal pool full of crabs and little jellyfish. I was totally focused, doing just one thing, observing the world and completely cognizant of time and space and my place in it in that moment. I breathed in. I breathed out. A chunk of anxiety dropped away, and I felt ready to face the world again. In that moment, I was reminded that there are indeed many paths to that calm, inner certainty some call mindfulness.

But I still might go back and get the book.

- Emily

A Visit to the Borderlands

Last week, we traveled to the borderlands of Arizona with dear friends. We visited a magical place called Hacienda Corona de Guevavi. It’s a beautiful bed and breakfast perched atop 36 acres of a historic mission and ranch along the banks of the Santa Cruz River, just miles from the U.S.-Mexico border town of Nogales.

Our hosts were a delightful family: a gracious, determined and spiritually grounded woman; her capable, enthusiastic and fun-loving partner; two adorable children; four dogs; a couple of horses; and a flock of chickens. In the owner’s own words, “While the old barn and rusty silo remind us of its rich ranching heritage, the Hacienda itself is elegant and quite refined...It's no wonder that John Wayne and other Hollywood luminaries were attracted to this cool, high desert location where they could hide from the world, rest, relax and have a little fun.”

We spent two peaceful nights in the Duke’s very own guest suite, sleeping under the stars. We ate some great meals with our hosts and traveling companions. We had cocktails, took photographs and made music on a rock wall looking out over acres of rangeland.

We also went to the town of Nogales to visit a portion of the infamous border wall. It was painful seeing the division and demise of a once vibrant community where family, friends, neighbors and co-workers happily lived on two sides of an invisible line that casually identified two countries.

Described by The New York Times as a “metal curtain,” the wall is 18 to 30 feet tall, depending on where you stand. It’s made of rusted steel tubes and plates with reinforced concrete, and covered with barbed wire. Constructed in 2011, the wall cuts through the center of town, forcing people to wait in long lines to make the trek from one side to another for shopping, doctor appointments, family visits, and work. Since much of our winter fruits and vegetables are grown in Mexico and shipped from southern Arizona, there are truck drivers whose sole business is to drive cargo from the border crossing to neighboring warehouses and then return an empty truck back to Mexico.

The wall has hurt the economy of Nogales, Arizona. A number of local businesses have closed; regional tourism is down; and the population of both the town and its county is dwindling.

On the other hand, in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, the population is growing. Some interesting local businesses thrive where Arizonans travel for less expensive pharmaceuticals, dental work, cosmetic surgery, haircuts, manicures, and restaurants.

The wall has divided friends, neighbors and families. I was told on Sundays, people gather on both sides of the wall for picnics and extended visits. You can see elders stretching their hands through the 4-inch gaps between the bars to touch their children and grandchildren. One woman sitting on a bench pointed to it and said to me, “El muro es malo,” meaning “The wall is bad.”

My time in Southern Arizona made me reflect on the notion of the “Borderlands.” In a book of his collected writings, Celtic author David Adam describes these marginal lands as “the edge of the familiar...and the known.” I think of them as liminal places where where the spirit of the land and its inhabitants (both past and present, human and otherwise) communicate with us through sight, sound, smell, touch and even taste.

The Borderlands reach beyond the known out to new horizons. They invite us to the edge of life as we know it, the space of possibilities. The Borderlands are the places where Jesus often stood: from the shores of Lake Galilee to the Emmaus road. The Borderlands are the locales where journeys are begun and ended - remember the great river crossings in all those bible stories.

The Borderlands are found in nature, in hospitals, in churches, in prison, at immigration crosses, and in country inns. These places on the edge call to us, inviting our exploration of the ebb and flow, the pain and joy, the paradox we call life. Sometimes, I feel like I’m living in The Borderlands of Dementia. It is no doubt a liminal disease, and I often feel like a stranger in a strange land as I cross to a wilderness that I don’t fully understand.

I left the Borderlands of southern Arizona determined to return. I want to go back to Nogales and take more pictures and have conversations with those affected by that awful wall. I want to see the story that the wall tells and listen to the voices who live in the shadows of that hideous concrete and steel manifestation of human fear and control. I also want to return to Hacienda Corona de Guevavi and soak in the gentle spirit of the land, the house, the barn, the rock wall, the animals and the people who live there. I might even invite some other friends to come along. - Tracey

Repairing the World - One Step at a Time

Excerpts from a sermon preached on the Third Sunday of Lent 2018

The Very Rev. Tracey Lind

All Saints' Episcopal Church, Phoenix, Arizona

John 2:13-22

In John’s Gospel, Jesus arrives in Jerusalem just before Passover. It was like the day before Christmas in a busy shopping district. The streets were bustling with activity: women picking up last-minute items for the Seder meal, children running around excitedly poking their heads in and out of shops, and men gathered in small groups talking about religion and politics.

The Temple was equally crazed. What should have been a place of prayer had been turned into a sprawling religious market, roughly the size of two football fields, with thousands of pilgrims, hundreds of merchants selling animals for sacrifice, and yes, the moneychangers.

In the first century, Jews had to make an annual pilgrimage to Jerusalem to offer ritual, animal sacrifices and pay the yearly temple tax. Because the tax could only be paid with shekels, Roman currency had to be exchanged, and the moneychangers demanded a ridiculous surcharge for this essential service. I liken them to check-cashing businesses or payday lenders.

In the Temple market, merchants supplied the sheep, oxen, turtledoves and pigeons certified by religious authorities to be acceptable for sacrifice in the Temple. What began as a service of convenience for out-of-towners had evolved into an abusive, expensive and exploitative practice, which today would have been exposed on the evening news.

On the days near Passover, the Temple was a three-ring circus filled with corruption – a corruption endorsed by the combined, synergistic forces of politics, religion and the market economy. No wonder Jesus got angry.

Most of us have experienced this kind of anger, hurt, loss, pain and angst. It might have been caused by childhood abuse or neglect. It might have been ignited by something that happened to us in school or a first job. It might have been instigated by something we witnessed in our parents’ experience or learned about by reading a book or watching a movie.

Jesus was angry that the Temple celebration of Passover, a feast of liberation, had evolved into a politically and religiously licensed activity of economic exploitation. He was angry that God’s sacred house had been turned into “a den of vipers.” His righteous, Passover anger led him to a passionate and fiery act of public engagement.

Can you begin to imagine the scene? It would be like someone coming into the national cathedral on a Sunday morning and turning over chairs, yelling at the preacher in the pulpit, upsetting the souvenir shop, and creating a general ruckus.

Jesus’ action in the Temple was a symbolic one. He knew that within a day or two, business would resume. Based on what happened to other Jewish rebels, Jesus also knew that he was putting himself and his companions at the risk of arrest and crucifixion.

Was this action successful? The answer depends on what Jesus’ intentions were. If he simply intended to get a reaction, to be recognized, he was successful. According to John’s Gospel, many came to believe in his power. If his action was intended to change the system, it didn’t do much good – at least, in the short-term. It was, however, an act of deep-seated, passionate anger by our Lord.

Anger is a complicated emotion, and it’s not one that we typically associate with Jesus. Yet, Jesus teaches us that anger is like fire: it can be used to clear a field, to rejuvenate it for the next planting, or it can destroy an entire forest. The fire ignited in Jesus’ belly was a hot, slow-burning fire, a long-lasting passion for peace and justice fueled by righteousness, grounded in prayer.

When I think of Jesus’ actions in the Temple, I recall the founders of our nation, remembering that this country was built on the foundation of a righteous rebellion that continued to evolve over two centuries. We are a country formed by revolution; so when you’re told that it’s not patriotic to demonstrate, don’t believe it.

When I think about Jesus’ actions in the Temple, I recall Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Sojourner Truth, Mahatma Gandhi, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Desmond Tutu and so many more who have taken action in the name of God’s justice. The fire of their angst was carefully built and tended to burn steadily.

And when I think of Jesus’ actions in the Temple, I see all those young people lying in front of our nation’s capital, saying “Enough” to gun violence and school shootings.

Through the eyes of a child.

As Jesus’ disciples, our mission is to plant ourselves at the gate of hope, outside the doors of the Temple, the place from which we experience the world both as it is and as it could be. We are called to stand there, telling people what we see and asking them what they see. And then sometimes, out of our angst, we are called to even greater action, taking the next step we never imagined, maybe even turning over a table or two.

For in doing what Matthew Fox has called “the small work within the Great Work,” we honor the God who brought us out of the land of Egypt and gave us freedom, and we follow the beloved Son of God who returned from the land of Egypt to give us new life. Amen!