The Gift of Humility

It’s been a busy few weeks. Two Sundays ago, we spoke at West Shore Unitarian Universalist. From the pulpit, Emily was able to thank Mary Jo, a woman in the congregation who had “dropped out of the sky,” and helped her so much in the beginning days of coming to terms with my dementia diagnosis.

Next, we traveled to Washington, D.C. where I participated in a panel discussion for the Us Against Alzheimer’s Summit. Taking my place as a dementia advocate with my friend and award-winning journalist Greg O’Brien who has Alzheimers, I was able to thank Greg who has taught me much about living with early onset dementia.

This past weekend, Emily and I traveled to Westford, Massachusetts, where at the invitation of Wellfleet friends and summer parishioners, Herb and Elizabeth Elliott, we spoke at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. It was a beautiful fall weekend, complete with New England color and seafood, as well as connecting with old friends and colleagues.

At our Saturday afternoon session, two women who had driven from northern Vermont to hear us, said that we had become their lifeline as they were dealing with a new diagnosis of FTD-PPA. They had seen us on Sixty Minutes; they had followed our blog, and they had read about us in the newspaper. Wow! We were blown away with honor and humility to realize that, like Mary Jo and Greg, we were helping somebody else along the path that we are traveling. It’s a very small world.

Jesus says: “All who exalt themselves will be humbled but all who humble themselves will be exalted.” (Luke 18.14) Want to learn about humility? Get a dementia diagnosis. That’s what happened to me three years ago when I was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Degeneration, a rare form of early onset dementia.

FTD has allowed me to learn about humility the hard way. For most of my adult life, I wore a uniform identifying my profession, had the best seat in church, held a place of honor at banquets, was greeted with respect in the marketplace, and people called me “Rev.” or “Dean.”

Then one day, it was over. The doctor told me that if my condition followed its usual course, in a matter of years, I would be unable to read, write, or understand language; then I wouldn’t be able to swallow; then I would die. He suggested that we should get our affairs in order, and I should make the most of my remaining time.

Within three months of my diagnosis, my career was history. The newspaper articles announcing my retirement were in the archives. I had bid farewell to my congregation and staff. My books and vestments were packed. I was without a title, office and church keys. My calendar was empty, except for a disconcerting number of medical appointments, and my email inbox was reduced to advertisements and listserve messages.

When that first Sunday of “retirement” rolled around, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I woke up late, read the paper, and drank a third cup of coffee. I thought about going to a local church, but instead, I sat in bed and wrote a poem, in which I described myself as “a little boat untethered on a big lake [with] wind and waves pushing away from familiar shore.” Like many newly retired and unemployed people, I didn’t know who I was without my title and position.

It’s hard losing your status and place in society; those of you who have lost jobs and/or spouses understand. It’s hard losing the identity you’ve taken for granted; certainly, immigrants and refugees in this country know what I’m talking about. And, it’s hard—really hard—losing your strengths; those of you who are struggling with health issues know of what I speak. To say, it’s humbling is an understatement.

I don’t think that humility was ever one of my strong suits. In fact, if I’m being honest, pre-FTD, I think I could have been characterized as being self-assured, and at times, a bit arrogant. But, when I started showing signs of cognitive impairment, my self-assuredness and arrogance quickly evaporated.

When you don’t know what day of the week it is; when you can’t remember whether you brushed your teeth, showered, or took your medicine; when you get disoriented in a crowd or startled on a busy sidewalk; when you stutter or shout, and use incorrect words or incomplete sentences in an effort to make yourself understood; when you become immobilized by choices and decisions; when you forget how to do a simple task; when you cross the street without regard to traffic; when you have a tantrum in public, burst into tears for no good reason, or even help yourself to food off of a stranger’s plate — pride goes out the window.

It is humbling to live with dementia. However, Jesus, who “humbled himself on a cross,” says that humility is a good thing. In fact, in the Gospel of Matthew, when instructing his disciples to take up his yoke and learn from him, Jesus refers to himself as “humble of heart.” (Mt 11.20)

Humility is considered a virtue, something to work towards or strive for. The Hebrew prophet Micah says, humility, accompanied by justice and kindness, is what God expects of us. (Micah 6.8) Benedict, the 5th-century founder of western monasticism, understood humility as the path, or “the ladder,” by which we ascend to “that perfect love of God which casts out fear.”

The Quran considers humility to be the highest knowledge. Thus it is written: “The servants of the Most Merciful are those who walk upon the earth in humility, and when the ignorant address them, they say words of peace.” (Surah Al-Furqan 25:63)

The I-Ching, the ancient Chinese guide for living an ethical life, explains the benefits of humility this way:

Yield and overcome;

Bend and be straight;

Empty and be full;

Wear out and be new;

Have little and gain;

Have much and be confused;

Therefore wise [individuals] embrace the one

And set an example to all.

Not putting on a display.

They shine forth

Not justifying themselves,

They are distinguished.

Not boasting,

They receive recognition.

Not bragging,

They never falter.

They do not quarrel,

So no one quarrels with them.

Therefore the ancients say,

“Yield and overcome.”

Be really whole,

And all things will come to you.

According to the perennial wisdom that crosses all religious boundaries, humility is a way of becoming whole and fully human. So what exactly is humility?

Day by day, I’m learning that humility is about both acknowledging and accepting what I can and cannot do. I’m learning this is truth in the adjustments and adaptations that I’m making to live with dementia. It’s hard, but it’s essential for my well-being and those around me. I’m also learning that as my strengths don’t make me more of a child of God, my limitations don’t make me any less of a child of God. In fact, coming to terms with both my abilities and my disabilities is helping me to find and claim my rightful place in relation to God and neighbor. It’s giving me new eyes to see Christ in the other. And, it’s changing my attitude about acceptance of myself and of others.

My colleague and friend Robert Morris once wrote that “true humility … is the fruit of a keen-eyed ability to see oneself realistically, as a flawed and gifted creature like all other human beings.” Quoting St. Paul, he reminds us that, “You should not think of yourselves more highly [or more lowly] than you ought to think.” (Rom 12.3) Morris continues: “When we humbly accept our own reality as it comes, we are better able to see the world as it actually happens around us. We then can see more clearly what’s called for the here and now regardless of what’s in it for us.”

So how do we cultivate humility? Well, I don’t think you have to get dementia. However, you do need to make an honest self-assessment of yourself. As the Pharisee learned in this morning’s gospel story, it’s not about justifying yourself in order to feel superior to someone else. Rather, it’s about accepting the good, the bad and the ugly, and realizing that it all comes from the dust, and to dust, it all (and we all) shall one day return.

In yoga, there is a position called “Child’s Pose.” It’s considered an “active” resting pose with knees bent, forehead on the ground, and arms stretched out in front. Whenever I find myself in Child’s Pose, I think of is as prostration, an ancient prayer posture. For me, “Child’s Pose” becomes a moment of prayer, a time of re-centering and reminding myself that the universe is a big place, and I’m one small participant in its grand story. Any way you look at it, getting down on your knees or flat on your stomach, placing your hands in front of your body on the ground, and lowering your head till your forehead touches the ground is a humbling action.

Almost without exception, when I’m in Child’s Pose, I also am reminded of just how hard it is for me to be humble. I identify with the 11th-century French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux who once said that rather than ascending the Benedictine ladder of humility with grace, he was better prepared to slide down it.

So true, so true. If we’re honest with ourselves, most of us fall or trip into our humility. I know that I have, and I bet you have or will have as well. The virtue of humility is a complicated thing. We all would be wise to give it consideration before it demands our attention. But when it does, and it will, if we accept it, this curse will become a gift and will lead us into the fullness of life.

Referenced Material: Benedict of Nursia, Rule for Monasteries 7:67, The Rule of St. Benedict, ed. Timothy Fry (Collegeville, Minnesota: the Liturgical Press, 1981), Tao Te Ching: A New Translation, Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English (New York: Vintage Books, 1972), Henri Nouwen, Bread for the Journey (1997), Robert Corrin Morris, “Meek as Moses: Humility, Self-Esteem and the Service of God,” Weavings, Volume XV, Number 3 (May-June 2000), M. Basil Pennington, “Bernard’s Challenge,” Weavings, Volume XV, Number 3 (May-June 2000)

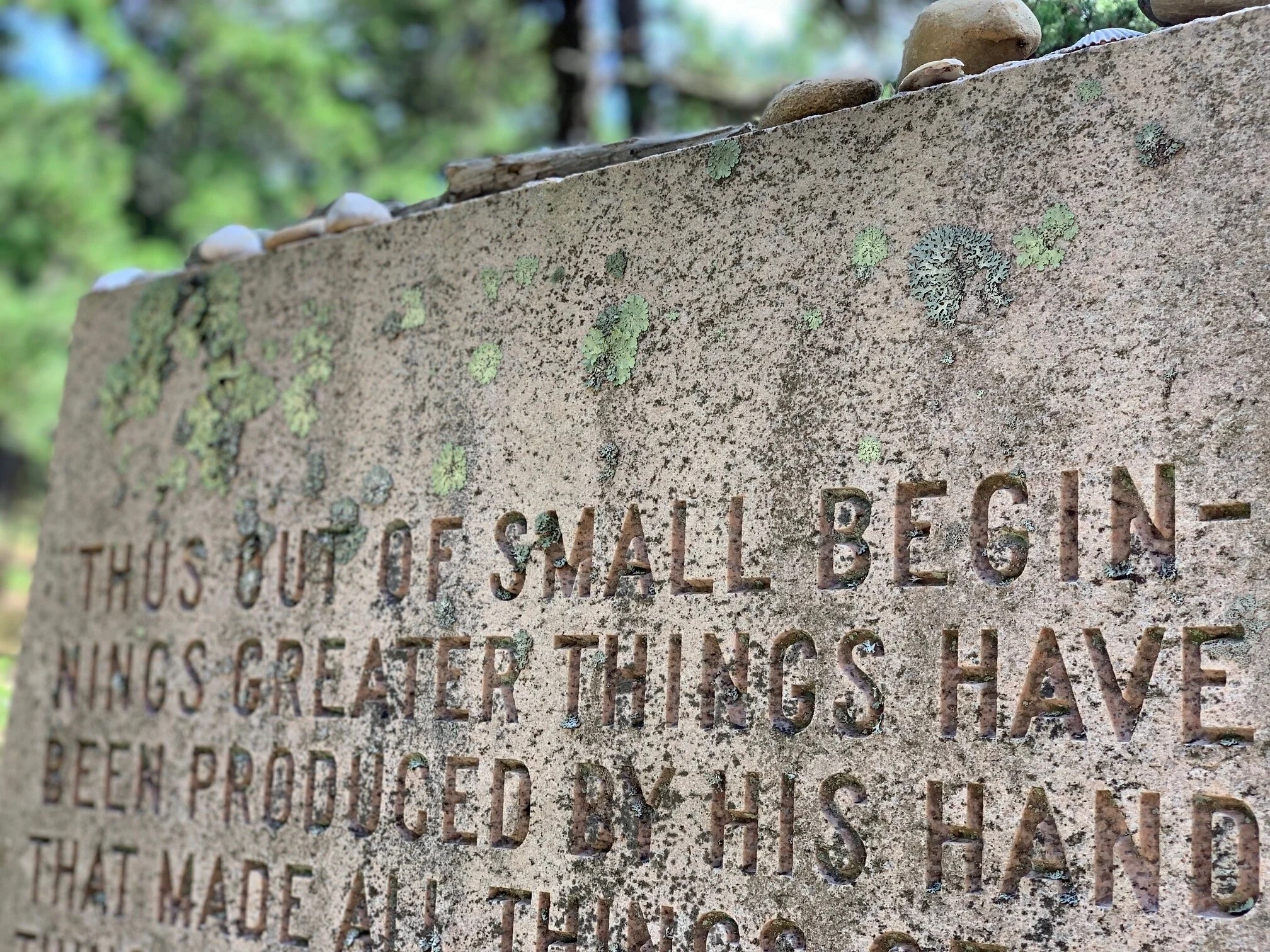

Be Like Mustard Seeds

Photo by Tracey Lind

I need more faith to face the days ahead. As I consider the state of our nation and the world, I am frightened. I fear for our children and their children.

I don’t want to live (nor do I want future generations to live) in a world devastated by war, poverty and global scorching. I don’t want to reside in a nation threatened with terror, corruption, and conflict. Yet this is the current landscape. We live in what the poet Sara Teasdale once described as “a broken field, plowed by pain.”

Our country is a fertile field that has produced many a blue ribbon, bumper crop. It is a land enriched by the blood, sweat and tears of “all sorts and conditions of people.” It is a land cultivated with the best technology and raw materials money can buy. It is a field of hopes, dreams and visions. In the words of singer-songwriter, Pete Seeger, “our land is a good land,” and our people are generally good people.

At the same time, our country is a field that wants attention. Our crops, while strong and vibrant, need pruning. Weeds of plenty crowd out fledgling seedlings. Stones of arrogance, self-aggrandizement, and divisiveness get in the way of the plow. Our precious land is being broken and ripped apart by terrorism, war, poverty, fear, greed, and hatred. Our nation, a land of immigrants, once a beacon of welcome, has turned its back on so many seeking to join us.

Where do we turn for hope?

I turn to the Hebrew prophet Habakkuk. Writing to the Jewish people during the late 6th century BCE, Habakkuk lived in a painful world in which justice never went forth except in what seemed to be a perverted form.

Distressed that violence and injustice prevailed in his land, he agonized over the thought that God would tolerate such evil. And so he prayed, “How long?” and asked, “Why?” He questioned God’s fidelity to the people because God seemed not to listen to prayer or react to the breakdown of society. From Habakkuk’s perspective, the almighty God was not willing to punish those who did injustice and violence to the weak and downtrodden.

In the first chapter of the prophet’s book, God answered Habakkuk’s prayers, cries and questions. But the answer was neither comforting nor reassuring. According to the prophetic response, God would use evil people to punish the evil and unjust behavior of his nation. God would rouse a mighty military force as an instrument to punish the wickedness of his country. They would impose justice, but justice according to their own perspective. In the process of punishing the wicked, innocent people would be killed.

Sound familiar?

Habakkuk did not understand. It seemed so unfair, so unlike the God of his ancestors, the God of the Exodus, the God of creation. Habakkuk wondered if there were any reason to still believe in God. Maybe God should be abandoned and traded in for a more tangible, more powerful, more relevant idol.

In his anguish and faithfulness, Habakkuk chose to wait for another encounter, another conversation with the Almighty. Eventually, God spoke again, and Habakkuk received divine insight. God answered:

Write the vision;

make it plain on tablets,

so that a runner may read it.

For there is still a vision

for the appointed time;

it speaks of the end, and does not lie.

If it seems to tarry, wait for it;

it will surely come, it will not delay.

(Hab 2:2-3)

Wait, be patient, have faith, and act.

God’s vision of justice and peace, and mercy is still alive today. God’s promise of reconciliation and redemption and salvation for all creation is still valid. God has not given up on us.

Therefore, God wants us to have enough faith and courage to “write the vision; make it plain on tablets, so that a runner may read it.”

Jesus elaborated on this message by calling us to have faith like a mustard seed. Whether growing wild or intentionally planted and cultivated, mustard is more than just a feast for the eyes. It's nourishment for the land and a feast for other crops.

Mustard plants thrive just until their buds break. Then they are turned under to mulch and provide valuable nutrients and phosphorus to the emerging plants, especially grapevines. Ancient farmers carried mustard seeds in a backpack with a hole in the bottom so that as they walked, they sowed and scattered their seeds with abandonment.

This is how Jesus wants us to live. As followers of an itinerant teacher, rabbi and prophet, we are called to spread his good news, through word and action; to have faith that like mustard seeds, our message will be prolific, spreading far and wide to nourish the land.

As the community of faith, we are commissioned to proclaim the prophetic vision for which Jesus gave his life: good news for the poor, release to the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, and liberty for those who are oppressed.

As those who promise ‘to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving our neighbor as ourselves, we are called to insist that God loves everybody regardless of race, gender, nationality, religion, or sexual identity; that God has a place for everyone at the table; and that God doesn't like it when we exclude others from God's love and God's table.

As those who follow the Prince of Peace, we are called to insist that God wants peace and justice, not war and terrorism; and that God wants us to become peacemakers and justice-seekers and to expect the same of our elected leaders.

As those who follow a savior who was born in a stable, lived among the poor and told the rich to share their wealth with the poor, we are called to admit that God has a special affection for the hungry, the homeless, the unemployed and the impoverished; and that God wants us to work on their behalf and vote for their well-being.

As those who love a Lord who raised up, embraced, beckoned the little children to himself, we are called to lift our voices on behalf of all God’s children; and to insist that all God’s children – rich and poor, black, white, yellow and brown, urban, suburban and rural – have a right to a decent education, safe places to live, and enough food to eat.

As those who know the healing presence and restoring power of God in Christ, we are called to insure the health and welfare of the wounded, the sick and the afflicted.

As those who have feasted on the abundant bread of life and have drunk from the ever-flowing streams of living water, we are called to share our abundance with the world around us.

As those who promise “to persevere in resisting evil,” we are called to speak the truth and to insist that our political, corporate, civic, and religious leaders do the same in justifying individual and collective actions.

As those who promise “to respect the dignity of every human being,” we are called to protect the rights of all, including the stranger and sojourner, the refugee and immigrant, and those who live behind prison walls.

As those who were given the stewardship of creation, we are called to protect our environment and to insist that our government and our corporations do the same for the sake of every living being, now and in the future.

Perhaps most importantly, as those who proclaim the risen Christ, who say, ‘We are an Easter people,’ who meet God on a cross and in an empty tomb – we are called to believe that this same God can overcome fear, divisiveness, and hatred; and to trust that God can break down the walls that divide us.

God is not a Democrat or a Republican; God is not a libertarian, a socialist, a communist, a member of the Green Party, or even an independent voter. God is not a member of any political party. Rather, God simply calls the community of faith to follow the teachings of Jesus and the prophets.

We are to use our faith – small as a mustard seed and yet large enough to move mulberry trees into the ocean. God calls us to raise our voices collectively and individually – at dinner parties, at work, at church, at the country club, at the barbershop and the beauty salon, on the street corner, at the grocery store, and at the voting booth. We are called to cry out for justice and peace, for truth and integrity, for respect and dignity for all God’s people, come what may and cost what it will.

In doing so, we will grow hope and new life in the broken fields plowed by the pain of terror, oppression, poverty, hatred, fear, and war. That’s a promise.

"You Don't Look Like You Have Dementia "

I met this man doing a photoshoot outside a church in Manhattan during New York Fashion Week.

I asked him if I could make his portrait.

He smiled and obliged. He was a fashion model, after all.

Who knows what “the Son of Man in all his majesty” might look like.

People often say to me, “Tracey, you don’t seem like you have dementia.” I bet some of you are thinking that right now. If you had seen me last Friday night, you would think differently.

We had gone to a neighborhood pub for dinner and live music with a friend. It was loud and chaotic. Soon after the music started, I felt a sudden and desperate urge to leave and go home. I whispered in Emily’s ear that I was going to walk home. Concerned, she started to call an Uber. I protested that it was unnecessary.

Without giving her a chance to stop me, I got up and left. Wearing flip flops, I started my 1.5-mile walk home in the dark. I tried to cross a complicated intersection and got a little confused. Some nearby folks on bikes yelled out, “Hi Tracey. Where are you going?” I responded, “Home.” They asked where Emily was, and I said, “At the restaurant.” They offered to walk with me, but I said that it wasn’t necessary.

They insisted and led me to a safer place to cross the busy street — a crosswalk, of all things. Then they walked with me for several blocks until they were sure that I wasn’t lost. I continued on my way in the dark. When I got home, I texted Emily and crawled in bed. I felt safe but exhausted. I was fast asleep when Emily returned. It had been a hard night.

Many of us (probably most of us) are really uncomfortable with the word “dementia.” In fact, we prefer to use words like: thinking problems, memory challenges, or mild cognitive impairment.

Why is the word “dementia” so loaded, and why do I choose to use it? We think of a person with dementia only in the advanced stage: almost entirely lost and bewildered, confused, limited, or incapacitated. That’s not me or others, especially middle aged adults, in the mild to moderate stages of brain disease.

I choose to use the word “dementia,” because if we are going to address this growing health crisis in a just and compassionate way — if we’re going to find causes and cures, and provide loving care, support and community for those living with dementia and our families — we have to name the elephant in the room. We have to de-stigmatize the word “dementia” and talk about it.

Denial is a common issue when it comes to dementia. People want to offer comfort by saying things like, “You don’t seem different to me. Are you sure you weren’t misdiagnosed? We all forget where we placed our phone or can’t recall a word or name.” But such well-intended remarks are neither comforting nor helpful, for they reinforce an unhealthy cycle of denial and doubt.

And as dementia runs its course, it becomes increasingly difficult to care for oneself, to act appropriately and to speak coherently. As our brain disease advances, we often end up in wheelchairs, and eventually in bed. At the end-stage, we are frequently unable to meet our basic needs, thus becoming very reliant on the kindness of others, even strangers.

Some might say, we become like Lazarus, begging for crumbs of time and attention, respect and compassion, care and concern, and perhaps, most importantly, friendship and companionship.

The parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus is based on an ancient Egyptian folktale about the reversal of fortune in the afterlife. Alexandrian Jews—perhaps including Jesus’ family, who spent a few years living as refugees in Egypt—brought this story to Palestine, where it became widely known as the tale of the poor scholar and rich tax collector.

In Jesus’ telling of the story, the Rich Man (often called by his Latin nickname Dives) was a member of the privileged class. He lived a life of leisure, wearing expensive linen, eating rich food and drinking fine wine.

Lazarus, the poor man, whose name in Hebrew means “God helps,” is the only character in all of Jesus’ parables with an actual name. He was a beggar with a bad skin disease that alienated him from society. Lazarus was so hungry that he ate whatever those who sat at the rich man’s table threw on the ground; to add insult to injury, the dogs competed for his crumbs and licked his oozing wounds.

According to first-century worldview, Lazarus got what he deserved. His miserable condition resulted from his sinfulness (or that of his parents), his predestined lot in life, his behavior, or some combination thereof.

Unfortunately, many Americans still think the same way about the poor, the homeless, the addicted, the undocumented, the blind, the lame, the chronically sick, the mentally ill, and even folks like me who are living with dementia. Bad things happen to good people, but we have a tendency to blame the victim or to view their condition with an element of shame, blame, and disdain. And all too often, we mistakenly blame and sometimes disdain, ourselves for our own condition or situation in life.

This parable may well be Luke’s take on the well-known passage in Matthew 25*:

When the Lord comes in glory, he will sit on a throne and separate the people.To those on one side, the Lord will say: “Come, you who are blessed by my God; inherit the kingdom prepared for you before the world began.

I was trying to order in a restaurant but was confused by the menu, and you explained it to me. I wanted a bottle of water from the vending machine but could not figure out how it worked, and you got it for me. I didn’t recognize your face, and you reintroduced yourself to me without making a big deal of it. I became overwhelmed trying to cross a busy intersection, and you offered your arm. I couldn’t understand how to operate the subway ticket machine, and you offered help. I needed a quiet place to swim, and you made it possible. I got confused in an exercise class, and you gently assisted me. I was scared in a TSA line, and you spoke to me slowly. I was lonely, and you came to my house and played music and games with me.

Then the righteous will reply: “When did we see you in such distress and respond with such compassion?” The Lord will answer, “Whatever you did for one of the least of these my people, you did for me.”

To those on the other side, the Lord will say: “Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.

For I stood at the deli line unable to make a decision, and you grew impatient with me. I tried to wash my hands in a public restroom and couldn’t understand the automatic faucet, and you pushed me out of the way. I attempted to buy a movie ticket, and you rushed me. I needed to sit down on the bus, and you wouldn’t give up your seat. I felt self-conscious as I stuttered and shouted to make myself understood, and you laughed at me. I hesitated at a traffic circle, and you tried to run me down. I had a melt-down in public, and you berated me. I was lonely and distressed, and you refused to visit me.

They also will ask: “When did we see you in such a state of distress and fail to respond with compassion?” The Lord will reply, “Whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me." Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous will go to eternal life.

Friends, we do have a growing crisis of dementia in our midst and a growing opportunity for compassion. We need our churches to be visible communities of acceptance, belonging, and concern where people living with dementia and their families can find a home of welcome and embrace.

When people with dementia and our spouses can no longer attend church, the congregation can come to us. When people with dementia can no longer remember who we are, others become our memory, not only reminding us of who you are but, if necessary, reminding us of who we are. When spouses and care partners are exhausted, friends, neighbors, and parishioners can offer support and respite.

When people with dementia find ourselves in assisted living facilities, friends, families, congregants and clergy need to visit, and caregivers must resist the temptation to infantilize us. When we are at the end of our lives, the church can advocate for our right to die with dignity and be present with us and our families.

And when we die, the church can embrace our grieving loved ones, the survivors of a long battle with an unrelenting enemy. The story of Dives in Hell and Lazarus in Heaven can be a mirror to examine your own life, attitudes and values. Don’t just ignore or pass by your Lazarus—whomever he or she may be.

Look into her eyes. Offer him a glass of water. Believe people when they share their truth. And extend your arm to be a safe passage for someone at the busy intersections of life.

*The paraphrase of Matthew 25 used here was inspired by a similar adaptation on www.bestforages.co.uk

A Sermon for 911

Image credit, Church of the Incarnation, Manhattan, NY

A Sermon Preached on September 11, 2019

Church of the Incarnation, New York City

Today, we commemorate three notable occasions: the 18th anniversary of 911; the life and ministry of Harry Thacker Burleigh, one of America’s most influential composers; and the beginning of our Church Pension Group (CPG) board year. These three events actually hold together in an odd sort of way, and I invite you to consider them with me.

Everybody has a 911 story, and our generation will forever be able to answer that question: “Where were you when the towers were hit?” Some of you were in the financial district, and others were in Episcopal church buildings around the country. As for me, I was at a retreat center outside of San Francisco for a CREDO clergy conference.

I had awakened early in the morning to go running; it was, after all, a health and wellness conference, and I intended to make a new start. I returned from my early morning run and walked into the refectory. My CREDO companions were still asleep. However, the kitchen staff was gathered in a corner of the room staring at a small television set suspended from the ceiling. With my first cup of coffee in hand, I wandered over, looked up at the TV, and saw smoke coming from the towers. I couldn’t believe my eyes, and then I heard the newscaster exclaim: “A second plane has hit the second tower!”

Stunned, I wandered out of the refectory and tried to call home to family and friends in New York and New Jersey, but I couldn’t get through; the phone lines were jammed. Desperate to share the news, I woke up some of my fellow conference participants and told them what had happened. However, like Peter on the morning of the resurrection, they couldn’t believe my words, so they ran to the refectory television to see for themselves. Then they, too, started frantically trying to call friends and family.

After breakfast, our CREDO conference faculty convened us in the chapel. We said prayers, and then were informed that, after consultation with CREDO and CPG leadership, we would continue with the conference. It was all we could do, they said. We couldn’t go home as air traffic around the country was suspended, so we might as well make the best of it and continue our work of health and wellness.

So there we were, navel gazing on a CREDO conference at a retreat center outside of San Francisco while the rest of the world was in turmoil. Despite the best efforts of the conference faculty, it was a conflicted and confused — and for many — a not very successful CREDO. Some wanted to stay and keep going with the program. Others (including me) desperately wanted to get home to our families, congregations and communities. How could we reflect on our personal financial, physical, spiritual and vocational health and wellness when the world was blowing up?

My most vivid memories of that conference include:

Groups of clergy standing in the cloister with cell phones to our ears trying to connect with loved ones far away

Watching that little television set in the corner of the refectory ceiling for news from the outside world

Listening to the sounds of military jets patrolling the night sky along the Pacific coast

Trying to get a photo ID so that I could fly home when the air space reopened (that’s a story for our cocktail hour)

Going to the San Francisco airport to get on the first flight out of town

Taking 7 connecting flights to get home

Finally, falling into Emily’s arms at 3 o’clock a.m. when my last flight landed

I have two other memories of that conference: one disconcerting, and the other one comforting.

The first — As some of us were working with Nancy Smith to make airline reservations for home, a member of the conference faculty said to me: “You know, Desmond Tutu would have stayed on this retreat.” I was so offended and angry as he stood in judgment of my decision to prioritize to my congregational, civic and family affections and responsibilities over my CREDO time. This past summer, I shared that story with Bishop Tutu’s middle daughter, Naomi, who responded: “I think my father would have wanted to leave as well.”

The second — In the middle of that awful week, as communities around the nation gathered in interfaith prayer services, our CREDO conference gathered to pray. We prayed for victims both living and dead, grieving families and communities, first responders, and government leaders. We also prayed for our nation whose sense of security and innocence had been shattered, and whose identity, values and resolve were being tested. And then we sang. We sang our hearts out well into the night. Thousands of miles away from the rubble that was once the World Trade Towers, a small group of Episcopal clergy were singing for our lives and the life of our world.

The heritage of singing — in both good and bad times — has been passed down through the generations. Miriam sang after crossing the Red Sea, and Deborah sang after defeating her people’s enemy. David praised God in song and his son Solomon sang of love. Isaiah wrote songs of exultation, Jeremiah lamented in song, and Zechariah sang as he rejoiced. Paul and Silas sang in prison, and the voices of heaven sang a new song of the lamb before the throne of God. And, as we heard in this evening’s gospel reading, Hannah and Mary sang when they learned of their pregnancies.

I have given a lot of thought to the power of singing since that day. We sing to celebrate and to grieve. We sing as we work and as we play. We sing to make the world smaller. We sing to drown out the voices of hatred. And sometimes, we sing to stay warm, awake and alive.

Singing is a powerful form of prayer. Perhaps that’s why St. Augustine once said, “To sing is to pray twice.”

Singing has always been a way of surviving the horrors of prison and torture. Perhaps, one of the most poignant examples of the power of song during fateful times was the final message of Etty Hillesum. Scribbled on a scrap of paper and thrown from a box car as she and her family departed for Auschwitz, this young woman wrote, “Tell them, we left the camp singing.”

Singing is also a powerful act of spiritual and political resistance. The early Christian martyrs sang as they faced lions in the coliseums. Striking workers sang outside the mines, mills and factories. African American slaves sang as they toiled in the cotton fields. The LGBTQ community has sung our way to equality. And, though I don’t know for certain, I imagine that our sisters and brothers walking from Central America toward our border are singing along the way.

One of the most powerful resistance songs is an old Quaker hymn that dates back to pre-Civil War North Carolina when members of the Religious Society of Friends suffered for their opposition to slavery. Its words spoke volumes about the power of song: “Through all the tumult and the strife, I hear that music ringing. It sounds an echo in my soul. How can I keep from singing?”

Where would we be without singing? I don’t know. My beloved Emily says that when she sings, it is the only thing she can think about; for her, singing gives her head a vacation from the cares and worries of the world. As I am learning first-hand, for people with dementia, singing is calming and comforting; it helps us to make connections and keep memories alive; and is one of the last cognitive faculties to go.

Harry Thacker Burleigh, whom we remember today, certainly understood the power of song. Born to a free African American family in Erie, Pennsylvania in 1866, Burleigh demonstrated an early passion for music as he learned to sing in local church choirs. In 1892, he earned a scholarship to attend the New York Conservatory of Music. There, he developed a friendship with the school’s director and one of my favorite composers, Antonin Dvorak. The two shared an interest in using spirituals and folk songs as inspiration for classical composition.

Following graduation, Burleigh was hired as the baritone soloist by St. George’s Episcopal Church on Stuyvesant Square. In 1900, he made history by becoming the first black soloist at Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue. He even sang a command performance for King Edward VII.

Burleigh was also an incredibly accomplished composer. Inspired by Dvorak, he focused much of his attention on adapting African American spirituals into classical arrangements for choirs and soloists. He is perhaps best known in the Episcopal Church for his arrangements of “Deep River,” “My Lord, What a Morning,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Go Down Moses,” and “Were You There.” I can only imagine what Burleigh would have written to commemorate 911.

As the publisher and custodian of The 1982 Hymnal and Lift Every Voice and Sing, CPG is indebted to composers like Harry Thacker Burleigh and entrusted with the task of keeping their music alive in the world and available to the church.

And on this 18th anniversary of 911, it is the church’s responsibility to remember that awful day, and to work very hard every day so that it might never happen again.

As we remember those who lost their lives and loved ones on that fateful morning of September 11, 2001, may we be comforted with words from one of Burleigh’s best known songs, “Deep River”:

Oh don’t you want to go to that gospel feast,

That promised land where all is peace?

Deep River

I want to cross over into campground.

May the souls of all the departed rest in peace.

Rules of Etiquette, According to Jesus

In the book Entertaining for Dummies, author Suzanne Pollak writes, “Most people invite the same two or three couples over for dinner, and what happens is that you end up talking about the same thing.” The boring results, she explains, is that, “the conversation just picks up where it left off at the last party…To keep the conversation fresh, Williamson suggests that one should “invite a scandalous acquaintance or an intellectual with something to say that everyone wants to hear.”

Now, I ask you, who would that be? Who would you invite to your next dinner party? A survey of recent college graduates reported that Jesus was at the top of their dream guest list.

I don’t know how popular Jesus actually was as a dinner guest, but I do know that our Lord liked parties and did a lot of “table talk.” Some of Jesus’ most significant discourses, miracles, radical acts and resurrection appearances take place at the dinner table or around a meal: the wedding at Cana, the feeding of the multitudes, the healing of the man with dropsy; the anointing by Mary Magdalene; the washing of feet; the institution of the Lord’s Supper; and my favorite, breakfast on the beach.

Jesus recognized that table companionship – those with whom we eat – made a powerful social commentary and a wonderful teaching opportunity. Our Lord believed and behaved as if all of life was a banquet hosted by God: a party with an open invitation, a table with many seatings, a meal overflowing with the variety and abundance of creation so that all the guests could be satisfied, and plenty of leftovers to be shared with those who for varied reasons couldn’t get there in time.

It was Jesus’ mission on earth to help us clearly see God’s intentions for the abundance of divine grace: to help us to understand and follow God’s rules for table etiquette, as much as (if not more) than we follow those offered by Ms. Manners, Emily Post or Amy Sedaris.

What are these rules, you might ask? They can be summed up in two words: humility and hospitality.

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus is an invited guest at a dinner party, a banquet given by a leader of the Pharisees. One phrase, “they were watching him closely,” leads us to believe that Jesus was probably the “scandalous acquaintance or the intellectual with something to say that everyone wants to hear.” Without a doubt, the host and other table companions were testing Jesus. And what did Jesus do?

First, he asked a provocative question about healing on the Sabbath. When he got no response, he then healed the man with dropsy.

After this, he agitated the situation further by commenting in parable on the seating arrangements. Waiting until everyone was seated at his or her various places of honor, Jesus told a story that could be interpreted on many levels: economic, social, political, and even theological — suggesting that those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.

After insulting the party guests, Jesus then insulted his host by criticizing his invitation list. “When you give a luncheon or dinner, don’t invite your friends and relatives who can reciprocate. Instead, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind who cannot repay you.”

Can you imagine such a scene? A recent college graduate, perhaps one of those surveyed, has her first major dinner party to celebrate her new high-powered job with a prestigious firm. She invites some of her potentially important colleagues and their spouses. She is ready to impress them with her new apartment, her new dining room furniture, her new tableware, and her newly acquired gourmet cooking skills. She also gets her dream come true — Jesus is among the invited guests. But there is one hitch; our hostess is not allowed to tell anyone who he is.

The dinner guests arrive. They have their cocktails and move to the dining room. Jesus sits quietly at the far end of the table while everyone chooses a seat.

Just as everyone begins to eat, Jesus first insults the guests for their jockeying for power spots at the table. And then to add insult to injury, he turns to the hostess and says, “Next time you have a dinner party, why don’t you invite the men living in the shelter at your church, or the assistants in your office, or the stranger you pass on the street, instead of these new colleagues you’re trying to impress.”

I don’t know what I would have done in her place. But I do know that if God is the host of Jesus’ dinner party, the parable suggests that God raises us up out of our own humility, and God humbles us out of our own arrogance and self-importance.

We are called to welcome the stranger into our community and our lives, and not just strangers who look and act like us; rather, we are to invite strangers who might be very different from us, but who none-the-less are invited to join the party.

A party is a risky act of faith on the part of the host who wants to offer joy and believes that his or her guests are worth the effort. It’s a risk for the host who doesn’t know if anybody will show up, too many people will show up, or there will be enough food and drink to go around. In hosting a party, we risk that we won’t have enough chairs for people to sit, that somebody might spill wine on our favorite chair, or break grandmother’s antique chair. There also is a risk that the guests might not get along, someone might say or do something inappropriate, or we might have to deal unexpectedly with someone’s pain or grief causing a guest to present him or herself more as a stranger than a friend.

The dinner party, as a metaphor for Gospel living, is not about cultivating a society of one’s own kind, or getting ahead through entertaining. Rather, the dinner party is about celebrating life with your neighbor, crossing the boundaries of race and class, and sharing the bounty of the harvest with those less fortunate than you. And may we all remember that in the giving and receiving of hospitality with humility, we might “entertain angels unaware.”