Lessons Learned while Traveling with Dementia

Emily Ingalls and Rev. Tracey Lind, Dementia Advocates

As we approach the gate area for our flight, Tracey turns to me anxiously. “You’ll go up and tell them, right?” So, I sidle up to the desk and murmur to the agent, “My companion has dementia. May we board with the early group?” They are always accommodating, and they aren’t supposed to ask, but it makes us both feel better to state ahead of time why two apparently healthy women need to pre-board.

Forgive me. I used to look at the pre-boarding people and scan for frauds who just want to make sure their carry-on luggage gets into the overhead bin. I now understand that not all disabilities are visible.

Travel is stressful and confusing for people with dementia, and it can be overwhelming for their care partners. Tracey’s response to travel and her increasing need for recovery thereafter have become two of the markers we use to gauge the progression of this disease. Traveling requires extensive effort and planning, far more than it used to, and there will come a point when it just isn’t feasible anymore.

According to Us Against Alzheimer’s Fall 2019 Pulse of the Community online A-LIST survey results, nearly half (48%) of dementia caregivers “found that a loved one had been afraid or overwhelmed by unfamiliar surroundings, and nearly four in 10 (38%) said a loved one had become anxious in a crowded place, triggering an unexpected behavior. In addition, 38% of caregivers said their loved ones could no longer physically handle traveling and vacations.”

Frontotemporal Degeneration (FTD), although rare overall, is the most common form of early-onset dementia, and it messes with the part of the brain that contains one’s filter, blocks background noise, and prioritizes information. Normally, our brains sift through lights, sounds, and other distractions that compete for our attention. Our frontal and temporal lobes are responsible for telling us what behavior is appropriate, helping us judge whether or not we are in trouble — and then deciding what to do if the answer is yes.

Imagine it’s Thanksgiving weekend, the busiest travel days of the year, and you are sitting in the sports bar at the airport. The bartender is moving around making drinks, talking to the guy next to you, and the waiter is walking back and forth behind you. The busboy clatters past with a load of glassware. There are four screens with four different games going.

Outside in the terminal corridor, the PA system is announcing flights boarding and passengers gone missing. A family with three small children and a screaming baby hurries past, having been delayed in the TSA line when the toddler refused to go through the metal detector. If your brain is in working order, you can tune out most of this and focus on Ohio State vs. Michigan.

If you have dementia, you can’t.

Everything comes at you with the same intensity at the same time — all of it, the screaming baby, four games, “welcome to our city, please watch your bags.” So, of course, your mind explodes. You go into a fetal crash position, arms over your head, hands on your ears. You want to cry and run away, but you don’t know where you are or how to get out of there. And your beloved care partner is staring at you, praying for divine intervention.

Traveling with early to mid-stage dementia does not have to be this way.

It is not as much fun as it used to be, but it is possible to get where you need to go without getting shredded in the process. Tracey and I run the airport gauntlet two or three times a month, and we have learned how to continuously adapt our expectations and plans to our abilities. It requires thinking through the entire process, door to door, ahead of time, trying to envision potential obstacles and worst-case scenarios — weather delays, longer lines than expected, missed connections — and how we might deal with them.

Between the onset of brain disease and the late stages in a skilled nursing unit, there are a lot of years when bucket list items are still possible, and shared experiences can still be enjoyed. As dementia advocates, Tracey and I are committed to sharing the truth and spiritual insights we’ve gained from a life complicated by dementia with as much of the world as possible, for as long as possible. So we travel. A lot.

Below are a few of the tips and tricks we’ve picked up along the way. I hope you will share your own in the comments below.

Emily’s Tips for Tranquil Travel

The goal is to get where you are going as smoothly as possible, with as little fuss and anxiety as possible. Anxiety undergirds dementia even on a good day. Travel is unlikely to be a good day. Give yourselves enough time to get through security calmly, yet minimize waiting time at the gate, to board the plane early and settle in while it is quiet, and then to disembark as quickly as possible when the plane lands.

A “dementia card” can be helpful to print and carry with you while traveling.

Travel with dementia takes more time and costs more money. Our days of running for the plane with 20 minutes between flights and changing terminals are over. These days, we plan ahead to decrease stress:

• Fly at a less busy time of day, one that allows time to get out of bed at a reasonable hour and follow your usual morning routine as much as possible.

• Book a direct flight whenever possible.

• Pay for seats closer to the front with a little extra space and fewer distractions.

Airport Security is a perfect recipe for a dementia meltdown — chaotic, crowded and noisy. TSA pre-check helps, as does Clear if you travel often.

• For people who are more disabled, there is TSA Cares. (855) 787-2227. Call 3 days ahead and tell them you are bringing someone who has dementia. They will meet you on the entry side of security and help you through. Some fine print is involved, which you can find here.

• Whichever security screening line you choose, make sure the two of you are together — don’t let anybody butt in between you. The care partner should go through the metal detector first. This allows you to catch your spouse before she wanders off into the concourse and disappears, leaving her belongings behind while you are still being patted down at the checkpoint.

Waiting for your flight also requires a strategic game plan. Once you have made it through security, you may have some time to kill before your flight boards. Find as quiet a spot as possible. If you have access to the airline club, that’s your best bet, but an unused gate area or the back of a coffee shop is also good. Find a place where you can’t see the screens, set back a bit from the concourse. Leave that spot when you have just enough time to saunter to your gate, arriving about five minutes before boarding begins.

When boarding is called, don’t be proud: go with the first group, the ones needing extra time or assistance. Get behind your companion, making sure she knows what seat she is in. It gives you an opportunity to slip one of your dementia cards (see below) to the flight attendant. Get your companion settled in a window seat, shade down, headphones on and playing her favorite music or movie on a tablet.

After you arrive at your destination airport, arrange for an easily identifiable location for your family to pick you up or take a car service or a taxi.

Do not opt for two trains and a bus to your lodgings unless you and your partner have both spent years riding those two trains (or ones that look just like them-- see “perfect recipe for a dementia meltdown”, above).

One last thing: I know you love your family/college roommate/fraternity brother and have stayed at their house before, but things are different now. Your companion and you need a private room and your own bathroom. If that is not available, book a room at the hotel down the road.

Now that you have gotten yourselves where you are going, greet everyone, and then go to your room, shut the door, and take a nap. You both will need it.

10RH: A recipe for joyful giving

Like many great ideas, necessity was the mother of this invention. It was 2008, the stock market had plummeted and everyone was feeling strapped, wishing for Christmas to be simpler and less expensive. So we came up with a few simple rules for family gift giving — every present had to be under $10, recycled, or homemade — otherwise known as the "10 RH" rule. Once the rules were communicated and agreed upon, everybody went to work.

Christmas Day arrived and all the joy of the season came with it. My mother made fudge, and then we wrapped up her barely-used collection of purses for every woman and girl in the family, and to the men, she gave a slightly used briefcase or backpack. My in-laws gave away very special items from their home and the room filled with shouts of glee as sons, daughters, grandchildren, and in-laws unwrapped precious books from childhood and special pieces of family furniture or silver that had been lovingly polished anew. The farmers in our family presented frozen pork chops and sausage from Ralph the 4-H pig, dilly beans from their garden, figs in earl grey tea, pickled quince and fresh eggs from a new flock of chickens. I gave photographs in recycled frames, and Emily made incredible batches of olives brined in her secret recipe of spices and oils. And nobody spent more than $10 on any gift.

We set up a table for a CD Exchange, and what was one person’s tired music became another’s great discovery. And then, over eggnog and olives, we had the funniest Yankee Swap and watched a family of adult women fight over a Jane Austin CD collection that ended up being a box without the CDs.

Financial necessity changed our family Christmas. Since then, Christmas has become more creative, thoughtful and less hectic. That holiday season changed our family attitudes about consumption and gift-exchange.

Gift-exchange is circular in its very nature. When a gift is given and received in love, both the giver and the recipient are blessed. Our Jewish sisters and brothers call it a mitzvah.

Gift-giving is a part of the holiday season. I believe that the holiday gifts we give and receive are really symbols and reminders of the greatest gift of all — the love of God freely given to all of us. As history has shown over and over again, that love overcomes everything, even economics.

As you prepare for the holiday season, whether you celebrate Christmas, Hanukkah, or Kwanza, I offer “10RH” as one way of managing expectations, finances, and energy while magnifying the blessings and love that we share.

Dementia: A spiritual lesson in forgiveness

When the wrong word comes out of my mouth, when I do something inappropriate in public, when I don’t recognize a face or can’t recall the name of a close friend or relative; when I get flustered, confused, agitated or angry at someone for no good reason; when I can’t follow through on a simple project or activity, when I forget to show up for an appointment or lunch date; or when I attempt to cross the street unaware of oncoming traffic, I have to ask for the forgiveness of others.

When well-intended people say inappropriate and hurtful things about my condition, or about dementia in general, or when because I’m doing well, they question the diagnosis, I have to forgive them.

I’m also working hard to forgive myself for the ways I took brain health for granted and neglected my own self-care as I cared for others. What if I had exercised or meditated every day; what if I had managed stress more effectively; what if I hadn’t worked such long hours or gotten more sleep. The list of “what if’s” goes on and on. Since I can’t turn back the clock, I need to forgive myself, even as I try to live a healthier lifestyle.

Coming to accept the new me and learning to live in the here-and-now, I also realize how important it is to forgive the hurts, betrayals and injustices of the past. My shrinking brain simply doesn’t have room for all that stuff. Carrying grudges and guilt can become a very heavy burden. Jealousy, resentment, envy, rage, and despondency are really toxic for our brains, our spirits, and yes, our souls. So as I cleanse myself from environmental toxins, I’m also trying to get rid of spiritual toxic waste. This requires me to forgive those who knowingly or unknowingly have done me harm, and to seek forgiveness for the harm I’ve done to others.

More and more, I’m discovering that forgiveness is pretty good spiritual and cognitive medicine. I’m also coming to understand that forgiveness actually makes room in our hearts and minds for joy, love, healing and new life. In fact, I think it is one of the key ingredients in the recipe for cultivating the fullness of life.

While forgiveness appears to be a simple matter of letting go and letting God, it’s not that easy. Or, as C.S. Lewis observed in Mere Christianity, “Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea until they have something to forgive.” I can think of no truer saying.

Forgiveness actually leaves me with lots of questions. How does one forgive the spouse who betrayed your trust, the employer who made unreasonable demands, the parent who was overly critical or unattentive, or the friend who neglected your friendship? And those are just the ordinary hurts of being human. What about the big stuff, like the Holocaust, slavery, apartheid, sex abuse scandals, political corruption, corporate greed, and environmental genocide? How do we forgive institutional betrayal, social damage, global abuse, and collective sin? Are there limits to forgiveness; if so, what are they?

To forgive, in Greek, means “to let go, or set free.” From the cross, Jesus prayed: “Abba-Father, forgive them,” (Luke 23.34) and then he let go and returned to God. By the way, biblical scholars dispute whether “for they don’t understand what they do” is a later addition to the text.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus taught his followers about forgiveness. In fact, when they asked him how to pray, Jesus taught these words: “Forgive us our sins and trespasses as we forgive those who sin and trespass against us.” (Luke 11.14, Matthew 6.12) He also insisted that what we release on earth will be released in heaven, and what we bind on earth will be bound in heaven.

When we forgive or ask God to forgive, we are seeking to let go of the burdensome hurt that we’re carrying, to release the burden of another, and thus re-establish a broken relationship. In essence, through forgiveness, we seek to move to a new place of freedom and liberation, of rest and peace, of healing and wholeness.

It’s hard to forgive, especially when we’ve been really hurt, insulted or demoralized. That’s why Jesus said that in order for us to feel fully human, we have to be able to forgive others, even — perhaps especially — those who hurt or offended us the most. Jesus insisted that there is no one undeserving of forgiveness, even if we can’t offer it.

I’ll never forget sitting with a therapist as I struggled to forgive someone who had really hurt me and my church. I kept insisting that I needed to forgive this person, but I simply couldn’t do it.

After listening to me talk about it for a few weeks, the therapist asked, “Why do you need to forgive him?” I was taken aback. Nobody had ever posed that question before. Stammering for words, I replied, “Because Jesus tells me so.” But I couldn’t do it. I was stuck.

For years, I kept trying to forgive this person, but with no success. The more I tried, the more angry, frustrated and hurt I became. It was as if I was carrying this guy around in my arms, like a dog that has stolen a glove and can’t put it down to fetch a steak bone.

Eventually, I sought counsel from another priest. After telling her my story and my stuckness, she said, “I’d like you to make a confession.” “Why?” I asked. “Because, you are not able to forgive yourself for allowing him to hurt you, and for not being able to forgive him.”

Now, that’s ridiculous, I thought. But I agreed to give it a try. So I got down on my knees and made my confession, asking for God’s forgiveness of me, the one who felt like the victim.

In keeping with the sacrament of reconciliation, my confessor offered “words of comfort and counsel.” She instructed me to pray for this person’s well being every day until I was no longer angry. I responded, “That will be very difficult, but I’ll try.” She said, “Don’t try; just do it.”

I began to pray every day for the one who had wronged me, and slowly but surely, my anger started to soften and my hurt began to dissipate. I also started to see that person in a new light, actually feeling some compassion and pity for him. But it took months — no, years — of prayer.

“How many times am I to forgive another...” asked Peter. “As many as seven times?” “No,” said, Jesus, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy-seven times” or depending on how you read the text, perhaps “seventy times seven.” (Matthew 18.21-22) Jesus understood how hard it is to forgive. That’s why he said it might take a while.

All of us have broken relationships, moments and places in our lives that require forgiveness. As we approach the holiday season, I would invite you to take the time to ask yourself: "Who in my life needs forgiveness?" And, I would encourage you to make that work part of your holiday preparation, maybe even consider it could an early present to yourself and someone in your life.

On November 14, 1940, the city of Coventry, England was bombed. The Cathedral was destroyed. The morning after, Provost Richard Howard declared that the Cathedral would be rebuilt as a symbol of faith and hope for the future. He also declared that the Cathedral would pray for their enemies. This decision led to Coventry Cathedral’s worldwide ministry of reconciliation.

In the midst of the rubble, the cathedral’s stonemason found that two charred medieval roof timbers had fallen in the form of a cross. He set them up in the ruins. They were then placed on an altar of rubble with the words “Father Forgive.” Other crosses have been made from the cathedral’s medieval nails and have been given to cathedrals around the world engaged in the work of reconciliation. Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland is a bearer of one of these crosses.

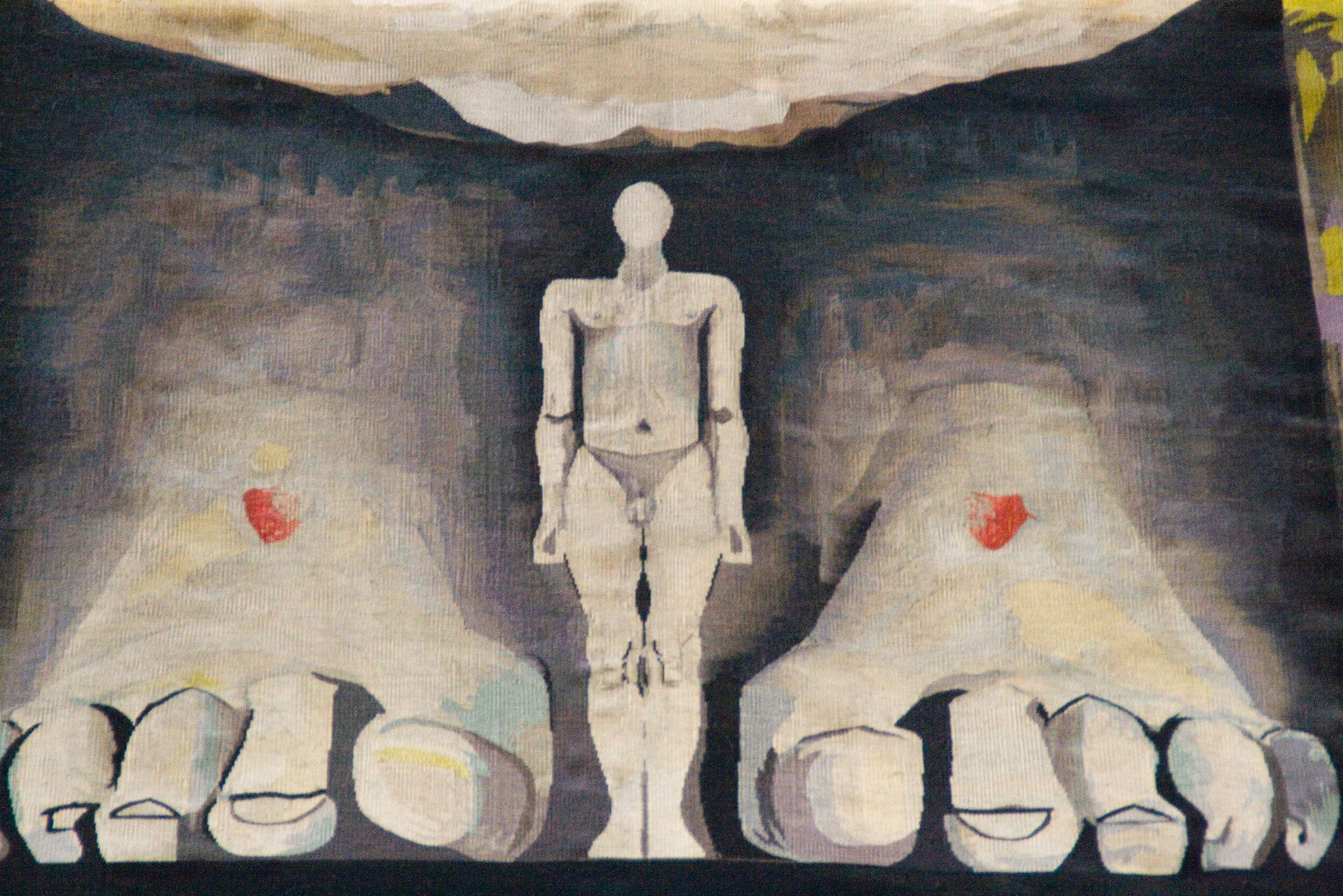

Emily and I visited Coventry Cathedral in 2007. These are photos from that visit. They remind me of the ongoing, difficult work of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Hey, God, Why All the Suffering? Reflections on the book of Job

There are some Bible stories that are so familiar that we think we know them, but we really don’t. The Book of Job is one of them.

The Book of Job is so challenging that I spent a week reading translations, both ancient and modern, commentary after commentary, as well as some amazing poetry inspired by this ancient text.

Job addresses the perennial question: why do bad things happen to good people. Where is God in our suffering? As liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez writes, “The Book of Job does not claim to have found a rational or definitive explanation of suffering.” It is a sacred text that leaves us with more questions than answers.

Written for a highly educated Jewish audience, Job is a dramatic poem bookended by a popular folktale. The prologue tells a story that sets the stage for a profound drama involving God, a member of the heavenly court named Ah-Satan (not to be confused with Satan, the devil), a righteous man named Job, his unnamed wife, his children, and his friends. The epilogue offers a settlement without resolve.

The storyline is simple. Job was a just, wise, humble and charitable man. His wealth and virtue aroused jealousy and curiosity in the divine consort. So one day, Ah-Satan (whose name derives from the Hebrew word for “obstruction” or “opposition”) asked God if he could test Job’s righteousness and fidelity. God gave permission but insisted that Ah-Satan not physically harm him. So Ah-Satan arranged for Job’s animals and children to be killed. Upon learning of his tragic loss, Job fell to the ground in grief but did not blame or insult God. In other words, he didn’t fail the test.

Not satisfied with this outcome, Ah-Satan returned to God and requested that he might test Job’s righteousness even more. Once again, God gave the go-ahead for further testing but again insisted that Job’s life be spared. So Ah-Satan struck Job with a terrible skin disease.

Upon witnessing her husband’s suffering, Job’s unnamed wife encouraged him to blame God, but our protagonist remained faithful. She then vanished from the story. Maybe she left Job in his time of need, maybe Job sent her away, or maybe she was struck down for lack of faith. We’re not told.

Four friends visited Job and offered consolation. They also urged him to give up his piety, but stubborn Job remained steadfast in his faith.

In the epilogue, God showed up, scolded the friends for their bad advice, and rewarded Job for his fidelity, giving him a new home, new fortune, a new wife, and new children.

The traditional moral of the tale is this: when you are faced with hard times, don’t be tempted to relinquish your faith in God. God has reasons beyond your understanding for what God is doing, and if you hold on to your faith long enough, God will reward you for your suffering.

We know this story and its teaching, all too well. It is a popular perspective on suffering. I’ve heard it over and over again in my ministry. I heard it as my mother was dying with dementia, and I’ve heard variations on it since receiving my own dementia diagnosis.

However, within the actual Biblical text, there is a very long and complicated poem that tells another story of Job. Sitting in the dust, surrounded by his friends, scratching his boils, Job cursed the day he was born and the night he was conceived. He then reproached God for his suffering. His friends, each in their own inept way, using traditional moral reasoning, tried to dissuade Job from getting angry with God. One insisted that he deserved his misfortune; another said that Job should not expect God to explain the divine self; the third accused Job of blasphemy; and the fourth suggested that God sometimes causes suffering as a form of character building.

In the midst of Job’s suffering, we find this passage, which contains words of comfort that we share at the beginning of nearly every funeral:

For I know that my Redeemer lives,

and that at the last will stand upon the earth;

and after my skin has been thus destroyed,

then in my flesh I shall see God . . . (19.25-26)

As comforting as these words sound at the graveside, that was not Job’s intention. Job was actually saying this: God, I’m an innocent man who is being falsely punished and tortured. Someday, my defender will show up and convince you that I don’t deserve this suffering.

Throughout the poem, Job insisted upon his innocence and maintained that he was being unjustly punished. Eventually, he had the audacity to use an old legal tactic with God: take me to court and produce evidence against me, or drop the charges.

Job’s words were so compelling and forceful that God responded directly to his summons. However, God didn’t address the issue at hand. Instead, out of the whirlwind, God asked: “Who are you to challenge me? Where were you when I created the world?” Thus commences one of the most powerful monologues in the Bible, basically informing Job of just how hard it is to be God. Talk about being put in your place.

In the ancient text, Job was taken aback by God’s forceful — perhaps, even bullying — presence and belittling words. He responded to God with frustration, exhaustion, and resignation:

How can I answer you without being disrespectful? I’ve already said too much.

I’m just gonna shut up. (40.4-5)

However, God was not finished talking with Job. Out of the whirlwind, God spoke again with power and might:

Man up!

I ask you:

Will you go so far as to breach my justice?

Accuse me of wrong so that you’re in the right? (40.7-8)

I don’t know about you, but I’d be quivering in my sandals. However, Job did not back down. In fact, he had the final word:

Truly I’ve spoken without comprehending

Wonders that are beyond me.

But I’ve heard you,

And now I’ve seen you. (42.3-5)

And here’s where the text gets complicated. The traditional interpretation is that Job’s final words express remorse and repentance:

Therefore I despise myself,

And repent in dust and ashes. (42.3-6 - NRSV)

Other scholars suggest that Job conveyed contempt toward and disappointment with God and compassion and sorrow for humanity. In his new commentary, Edward Greenstein of Yale University offers this translation of Job’s last words:

I am fed up; and

I take pity on dust and ashes (42.3-6)

Greenstein insists that Job did not acquiesce to God, but rather, he expressed “disdain for the deity” and “pity toward humankind.”

In the end, Job came to accept that suffering is part of life and that God sometimes allows it or chooses not to stop it. He also concluded that God is beyond human understanding and accountability. And he learned that God shows up in the midst of suffering. But was Job remorseful or resentful? We don’t really know.

Did he ever make peace with God? We don’t know that, either. However, in the epilogue, after Job is restored to good fortune, he interceded with God on behalf of his old friends.

Whether or not Job and God were reconciled remains a mystery. But this much we know: God permitted his servant to be tested, and God allowed him to suffer. God met Job in his anguish, spoke to him with directness and candor, listened to his words, restored him to good fortune, and answered his prayer of justice and compassion for his misdirected companions.

Regardless of how God allowed his suffering or how his friends reacted to it, Job didn’t give up or give in. Rather, in the words of Elie Weisel, who witnessed and experienced the most extreme form of suffering in the Holocaust, “In solitude and despair, [Job] found the courage to stand up to God. And to force [God] to look at His creation.”

What does the story of Job say to those who are suffering in body, mind, or spirit? In the first place, we learn that it’s not our fault. Bad things happen to good people. Why? Who knows? Your guess is as good as mine.

Secondly, we learn that it’s okay to get angry, even at God. God can handle our emotions, including anger. As a community organizer, I learned that while it’s not healthy to be consumed by rage, anger is an essential ingredient in productive and creative action. When I was diagnosed with dementia, both Emily and I got angry, and it took time for us to move beyond our anger. But out of that anger has come acceptance and new life.

Thirdly, we learn that friends and family, well-meaning as they want to be in their concern and support, often don’t get it, and thus say all the wrong things. As Job’s friends and family never seemed to understand, sometimes it’s more supportive and helpful to just be present and listen rather than to offer misinformed consolation and misguided advice.

Finally, we learn that perhaps God, who is beyond all human understanding, whose ways are clearly not our ways, doesn’t or can’t stop what has been put in motion. Perhaps God is not all-powerful but rather all-present and all-loving.

There’s a story from the Holocaust that illustrates this point. An old man was digging out a filthy latrine as a Nazi guard stood over him. The guard said to the old man, “Now, where is your God?” The old man replied, “Right here in the muck with me.”

I don’t blame God for my condition. God didn’t cause it. However, I want and need to believe that God is in the muck with me and will not abandon me as my dementia advances. Like Job, whose faith, wisdom, endurance, and chutzpah offer me comfort and encouragement, “I am convinced that my redeemer lives and at the last will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, then in my flesh, I shall see God.”

And when I do, I have a lot of questions to ask.

References - For thoughtful perspectives on The Book of Job

Edward Greenstein, Job: A New Translation (2019)

Elie Wiesel, Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits and Legends (1976)

Harold Kushner, What Bad Things Happen to Good People (1981)

Dorothee Soelle, Suffering (1975)

Gustavo Gutierrez, On Job: God Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent (1987)

Gerald Janzen, Job: Interpretation Commentary (1997)

Anna Kamieńska, “The Second Happiness of Job et al” Astonishments: Selected Poems (2018)

John Berryman, “From Job,” Poetry Magazine (April, 1980)

Robert Frost, “God’s Speech to Job,” A Masque of Reason (1945)

James Parker, “And Job said unto the Lord, ‘You Can’t be Serious’” (The Atlantic, September 2019)

AFTD & Don Newhouse: Hope in Action

Many of the unexpected gifts that come with a dementia diagnosis have come in the form of unexpected relationships with people from all walks of life. Don Newhouse, a passionate and generous supporter of the Association of Frontotemporal Degeneration, is one of those people. His commitment to research and advocacy in honor of his late wife, Susan, and his brother was the subject of a recent article highlighting the AFTD annual Hope Rising gala, which took place last month.

Read the full story here, originally published on wwd.com and Yahoo! Lifestyle

“She’s fine. She just has a little difficulty speaking, but she’s fine. Some memory issues.” Donald Newhouse typically offered that response to friends who asked about the health of his wife Susan, then showing early signs of personality change. As it turned out, his beloved Sue wasn’t fine. Rather, she was in the early stages of a horrific neurodegenerative disorder, primary progressive aphasia, a variant of frontotemporal degeneration. FTD is a dementia which, while rare, is the most common form to hit people under age 60. It hits hard. Susan Newhouse was afflicted for 15 years, until her death in 2015. In a sad coincidence, the same disease struck her brother-in-law S.I. Newhouse Jr., who died two years later.

Their progressions toward death were surely devastating for the Newhouse families. I know because a related disorder struck my mother at a young age, fully robbing her, also over the course of about 15 years, of movement, speech, her personality. Memory? We’re not sure. She lost her ability to communicate. When her diagnosis finally came, it registered as both a shock and an enigma; everyone has heard of Alzheimer’s, but few people, myself included, could claim familiarity with cortical ganglionic basal degeneration.

Such disorders are little known and lightly understood. Officially, FTD afflicts an estimated 60,000 Americans, although the disease is almost surely underdiagnosed. Like my mother’s related malady, it is an awful scourge that steals its victims’ powers of speech and movement and can have devastating impact on behavior.

It is a disease, or more accurately, a cluster of diseases, crying out for more attention. Attention such as that it will receive tonight when the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration holds its Hope Rising Benefit at the Pierre Hotel. Newhouse is the evening’s chair and Anna Wintour; David Zaslav, ceo of Discovery, and Katy Knox, president of Bank of America Private Bank, the co-chairs. The evening’s honoree, Bank of America ceo Brian Moynihan, will receive the Susan & Si Newhouse Award of Hope..

Clearly Donald Newhouse is fiercely committed to the cause. After a doctor connected him with AFTD, he became a passionate supporter, and pushed to hold a high-profile benefit in New York. The event is now in its fourth year. In a Sunday morning conversation, Newhouse is open about his experiences with the disease, and suggests a further conversation with Susan Dickinson, AFTD’s ceo. “My wife had it for 15 years. I lived with it,” he says. “My brother was diagnosed with the same dementia and he lived with it for four years. So I’m deeply interested in doing something that would lead to others not suffering as I suffered with them.”