Can these bones live?

“Can these bones live?” God asked the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel. Standing in a valley of dry bones, Ezekiel, once described by Elie Wiesel as “the prophet of imagination,” responded, “God, only you know the answer to that question.” Out of the valley of dry bones, God created life anew.

I always loved Trinity Cathedral’s sunrise Easter Vigil, especially how the prophecy of Ezekiel was presented: for several years, we had a skeleton called “Chubby” narrate the story. For a few years, someone told the story while rattling dice in her hands. Another year, we had sand, lots of sand. And every year, we ended the story with the singing of the spiritual “Dem bones, dem bones, dem dry bones.”

Dry bones can be enfleshed and resurrected to new life. Last spring, when I retired, I felt like a bag of dried up bones, until I recalled the wisdom of Frederick Buechner who said "vocation is the place where our deep gladness meets the world's deep need.” God helped me to look at the passion buried deep inside and at the need of world around me, and then imagine beyond the obvious to find a new life, an enlivened spirit, and yes, a new chapter of ministry.

While on last week’s preaching and teaching trip to Washington State and British Columbia, I read Into the Magic Shop: A neurosurgeons quest to discover the mysteries of the brain and the secrets of the heart. In Lancaster, California, a city located in the western Mojave Desert, physician and author James R. Doty describes how, as a young boy, he met a woman who taught him the secret to making a good life out of miserable conditions. Her “tricks” included the basic wisdom and techniques of meditation: relaxing the body, taming the mind, opening the heart, and clarifying intention. Dr. Doty - an esteemed neurosurgeon, medical school professor, philanthropist, entrepreneur, and director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research at Stanford University - credits her “magic” with allowing him to visualize a future beyond obvious expectations, and giving him the courage to take risks and feel secure, regardless of the outcome. I wonder: is this what God taught Ezekiel to do as he stood in the Valley of Dry Bones?

Over the last two years, I’ve encountered a number of wise teachers and healers who have helped me visualize a future beyond obvious expectations. It’s truly amazing how effective and powerful this magic can be.

This past weekend, much of the world witnessed a wedding where a duke, an actress, a gospel choir, a cellist, a prince, a yoga teacher, a queen, a bishop, and a whole host of famous and ordinary folk came together, creating magic beyond obvious expectations, and in doing so, maybe gave this broken and frightened world the courage to take some risks toward a new and better future.

Many of the positive experiences that have happened in my life over the past year came to me through the "magic tricks" of contemplative prayer, self care and an open heart. I believe we can all use more of that kind of magic in our lives. With that in mind, here are some questions I hope you'll contemplate for the week ahead:

What and where are the dry bones in your life?

What new future beyond obvious expectations can you imagine?

What “magic tricks” do you need to practice?

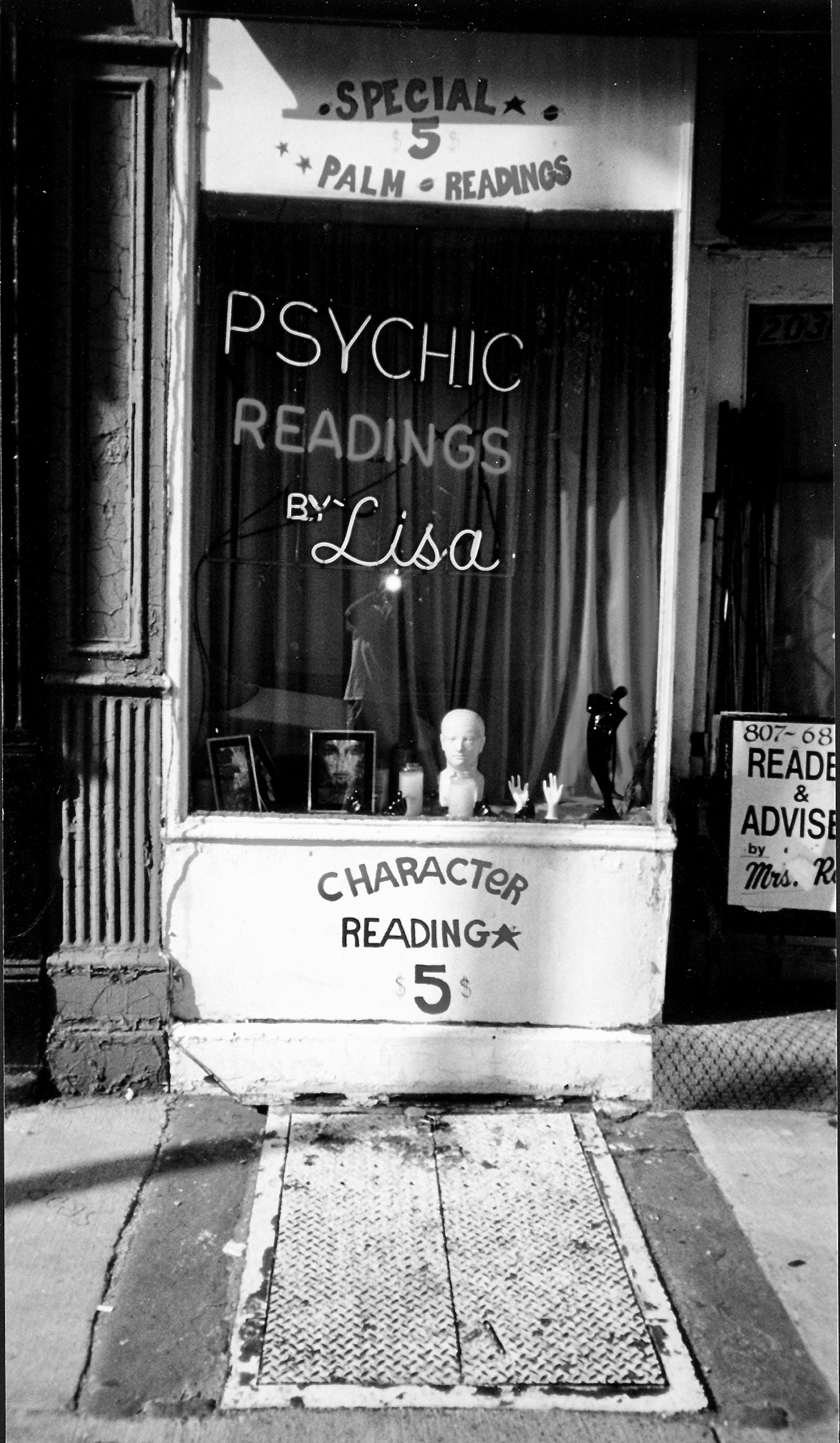

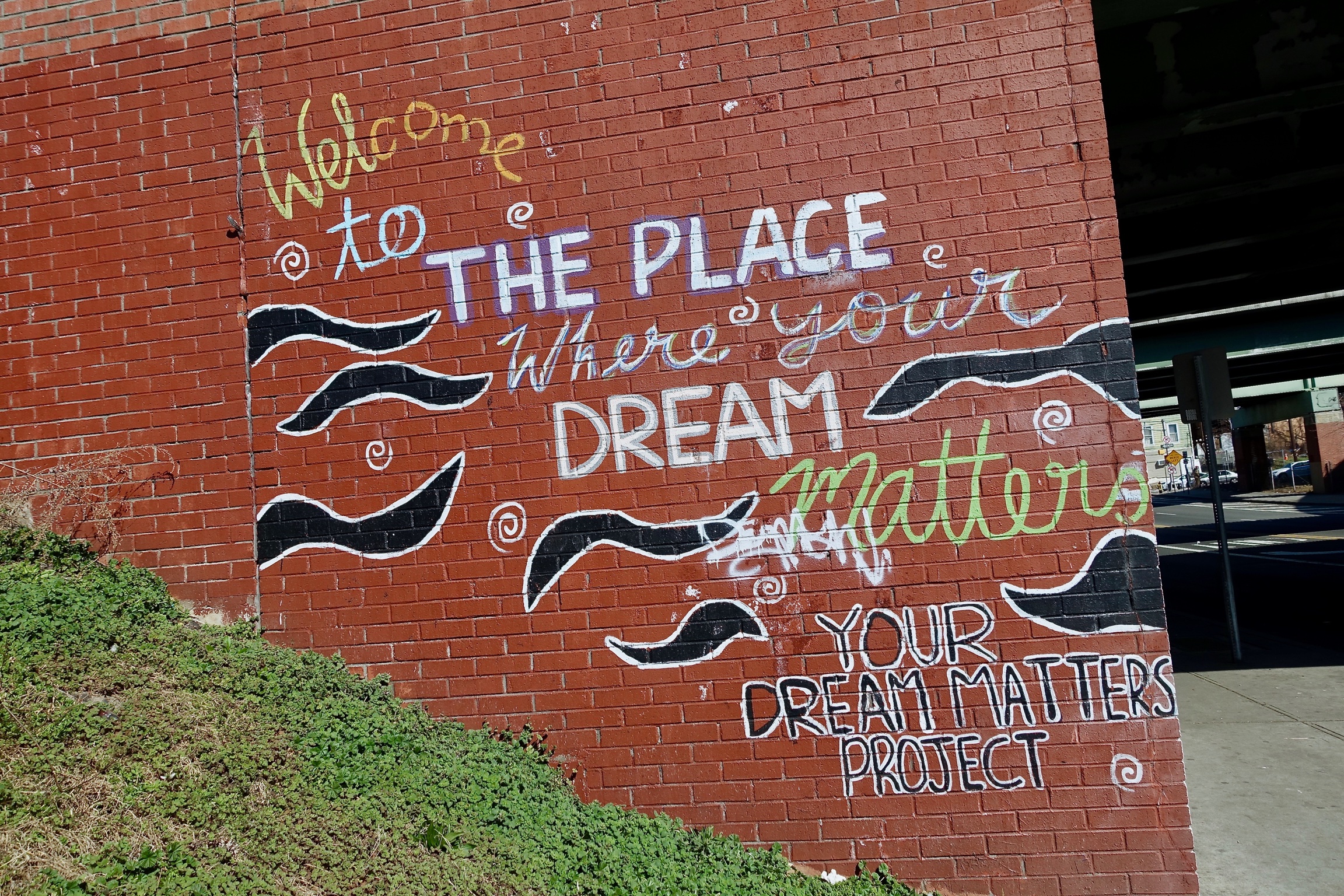

As you ponder these questions, I hope you enjoy some photographs that spoke to me this week.

Choosing Joy

For reasons hard to explain and even harder to comprehend, I have been more joyful in the past year and a half than ever before in my life.

Wanting to understand how I could experience so much joy while living with the dreaded diagnosis of dementia, I posed my question to Archbishop Desmond Tutu and His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, by reading The Book of Joy, the account of a weeklong conversation between these two great spiritual masters. Both now in their 80s, they have witnessed and experienced more than their fair share of trials and tribulations. And yet, Archbishop Tutu and the Dalai Lama are two of the most joyful human beings on the earth.

They define joy as an approach to life and a way of being in the world that radiates even in the midst of hardship, pain and suffering. The spiritual leaders concluded that suffering is both an unavoidable aspect of life and a required ingredient in the recipe for joy.

Archbishop Tutu and the Dalai Lama also agreed that joy is a by-product of our own actions and attitudes, regardless of our circumstances. Over the course of their weeklong conversation, they concluded there are eight pillars of joy: perspective, humility, humor, acceptance, forgiveness, gratitude, compassion and generosity. I’m now using these lessons in daily life.

My decision to reframe my dementia from an intrusion to an invitation, from a death sentence to pilgrimage, has helped me discover and cultivate joy in this new chapter of my life. I’m also coming to believe that joy is a key factor in helping me to manage and slow the progress of my condition.

As I enter this brave new world of dementia, I am deeply humbled by the courage, dignity, determination and joy of those who are living both independently and in memory units. I am honored to call them sisters and brothers, even when their dementia causes them to behave in ways that make me uncomfortable.

As my spouse Emily and I remind each other on a daily basis — when the wrong word comes out of my mouth, when I say or do something inappropriate in public, when I get flustered, when I can’t find my phone, my glasses or my hearing aids for the upteenth time, when I change my clothes several times in the morning, when I can’t get out of a chair or stumble over my feet, and when we have to go to one more doctor’s appointment — if we don’t laugh on this journey with dementia, we will cry. And there are days when we do both at the same time.

When I deny the reality of my dementia, grieve the lost aspects of my old identity, and resist the emerging aspects of the new me, I get tied up in knots; but when I accept what has died, let go of what has been lost, and celebrate what is being reborn, I start discovering surprising gifts and strengths, a different kind of balance and a new and more joyful way of living in the world.

As I walk this pilgrimage with dementia, I realize how important it is for me to forgive the hurts, betrayals and injustices of my past. My shrinking brain simply doesn’t have room for all that stuff. So, with each step, I’m trying to forgive those who have done me harm, and to ask for forgiveness for the harm I’ve done in my life. More and more, I’m coming to realize that forgiveness actually makes room in our hearts and minds for joy and love.

While I would have never, ever wished for this diagnosis, in a strange way, I am grateful for it. Dementia has opened up my world in ways beyond my imagination. It has helped me to see the preciousness and uncertainty of life. It has provided Emily and me with a new adventure in togetherness and introduced us to new friends all over the world. My condition has forced me to slow down and smell the roses. It has humbled me. And, It has called me to what others say might become the most important chapter of my ministry. I’ve decided to view my dementia in a way similar to how the Dalai Lama refers to his exile, as “an opportunity to get closer to life.”

One of my daily spiritual practices is to offer gratitude, trying (to the best of my limited, short-term memory) to name those people, places, and moments that have been there for me during the day. And that practice is most important to my well being and most meaningful on those days when I’m not feeling very grateful.

I get asked all the time why am I traveling so much in my "retirement." Isn’t it exhausting? Isn’t it painful? Isn’t there anything else I’d rather do? And the answer is yes and no. The preparation, logistics and travel can be very tiring. And talking about dementia (especially the injustices and the end-stages) sometimes makes me sad. But honestly, there isn’t anything else I’d rather do. It’s a privilege, a joy, and good “medicine” for my brain to explore the spirituality of dementia, advocate for people living with dementia and help destigmatize this dreaded disease.

And I hope you will find and cultivate joy in your life. But first, read, mark and inwardly digest The Book of Joy. You’ll find it a very helpful guide. - Tracey

Photos, left to right: Beach Lady - American Beach, Florida - 1997, Gay Games 9- Cleveland - 2016, A Grandson’s Smile - Santa Fe - 2005, True Love - Cleveland - 2009, A Patriot - Santa Fe - 2005, Hello Everybody - Cape Breton, NS - 2007, Bubbles - Santa Fe, NM - 2005, Header Photo: Here I am world - Madrid, NM - 2005

Keep on Singing

When I lived in Paterson, New Jersey, I would walk around the neighborhood on Sunday afternoons and hear shouts of joy and songs of hope coming from storefront churches. At first, I would get uncomfortable. I didn’t trust the emotions that I heard. How can these folks be so joyful and hopeful amid all the poverty and pain around them? I thought their ecstasy was sheer escapism.

Then I heard Presiding Bishop Michael Curry talk about African American spirituality. “Why didn’t slaves go crazy?” Curry asked. “They had no doctors, no therapists, or social workers. Even families were separated and sold. I believe it was their singing. Spirituals took away their shame, wiped away their tears and made them part of God’s own family.” Their singing freed their spirits in the midst of captivity, fed their souls in spite of physical hunger, healed their wounds of abuse, sustained them in the wilderness of oppression, and even guided brave souls to freedom.

The heritage of praising God, the sacred memory of jubilation – even in the midst of oppression, pain and trial – has been passed down through the generations. Miriam sang after crossing the Red Sea, and Deborah sang after defeating her people’s enemy. David praised God in song and his son Solomon sang of love. Isaiah wrote songs of exultation, Jeremiah lamented in song, and Zechariah sang as he rejoiced. Hannah and Mary sang when they learned of their pregnancies. Paul and Silas sang in prison, and the voices of heavens sang a new song of the lamb before the throne of God.

We sing to celebrate. We sing to grieve. We sing as we work. We sing to pray. We sing as we hike. We sing to make the world smaller. We sing to drown out voices of hate. And sometimes, we sing to stay warm, awake and even alive.

Where would we be without singing? I don’t know. Emily says that when she sings, it is the only thing she can think about; for her, singing gives her head a vacation from her cares and worries.

I have always loved to sing, and I am told that I usually sing a little off-key but with lots of gusto. When I was in school, we had to go to daily morning chapel. We would all line up in the hallway by class and height where we would be inspected for appropriate skirt lengths, clean blazers, and polished saddle shoes. If any one of these items were not in order (especially the length of our skirts), we would be sent home to redress and marked tardy for school. Then, those who survived dress inspection, would process into chapel singing a variety of familiar hymns, our favorite being, "For All the Saints."

When it came time for graduation, our class selected this same hymn for the processional. And so, on June 12, 1972, twenty-nine girls marched down the aisle in long white dresses, carrying a dozen red roses with tears in our eyes singing at the top of our lungs: “O blest communion, fellowship divine! We feebly struggle, they in glory in shine; yet all are one in thee, for all are thine, Alleluia, alleluia!”[vi]

Whenever I hear this hymn, I think about my school days and laugh. There we were a bunch of kids singing about the saints. We didn't know anything about the saints, and we certainly didn't think we were saints, much less behave like saints, and yet, we were drawn to sing about them. Now, when I think back on those days, I realize that we were what novelist Anne Tyler phrased, "saints maybe."[vii] We were, each and every one of us, potential saints. And only time would tell what would become of us. My and I classmates grew up. We became doctors, lawyers, writers, accountants, teachers, artists, civic volunteers, and ministers. We grew up to wives, lovers, mothers, and yes, grown-up daughters.

Singing has been an integral piece of my journey as a “saint maybe.” I have a song notebook (lyrics and guitar chords) in my own unique chronological order, and every song in my well-worn blue notebook reminds me of a particular phase, relationship or event in my life. On pages wrinkled with use and yellowed with age, there are lots of folk songs that I sang with my junior high friends in our band, The Checkerboard Squares: Wheat Checks, Rice Checks, Corn Checks, and Dog Chow (that was me). In the middle of the notebook, there are protest songs that I sang during my college years. Throughout the binder, you will find falling-in-love songs and breaking-up-is-hard-to-do songs (one or more for each relationship). There are the mountain songs and bluegrass melodies that I sang as I claimed my maternal roots. These are interspersed with the songs of the women’s movement that I learned during graduate school. And needless to say, there are songs for folk masses and youth groups, the music that brought me to the Episcopal Church in high school.

The Checker Board Squares - I’m “Dog Chow” without my guitar.

The most important songs in my notebook comprise what I call, My Coming Out Collection. This is the music that helped me claim the deepest, most intimate, and maybe the most complicated aspect of my life – my sexuality. One might say that I came out to music.

Now, I’m singing to keep my brain alive. We’ve all read how music and memory go together. I’m playing and listening music daily. Music is so important to my spirit that I’m making a playlist for when I can’t remember the songs I love including: childhood lullabies, high school favorites, falling in and out of love songs, protest songs, mountain songs, coming of age songs, coming out songs, hymns, road music, yoga favorites, and the great classics of the baroque, rock ‘n roll, motown, and bluegrass.

A long time ago, I made a promise to God and myself: no matter what happens, come hell or high water, no storm will shake my inmost calm, for I’m gonna keep on singing, all the days of my life. - Tracey

Parts of this blog were excerpted from my book Interrupted by God: Glimpses from the Edge.

A Pilgrimage with Dementia

It’s been two years since, in the words of Dante, “I came to a dark wood wherein the direct way was lost.” Emily and I have covered a lot of territory on this journey - literally and figuratively - travelling in three-month segments, like the old quarter schedule in college.

Three months of testing that led to a diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment (translate: they weren't sure what was going on)

Three more months of testing and therapy that resulted in a diagnosis of early stage dementia, probably FTD

Three months of wrapping up my career and bidding farewell to Trinity Cathedral

Three months of grief, relief and escape, including a 2,000-mile road trip and a 4,000-mile ocean voyage.

It has been an extended season of both physical and spiritual traveling. After crossing the ocean during Holy Week last year, I found myself ready to face this new chapter of my life, realizing that I wanted to transform this unwanted interruption from a death sentence to a pilgrimage.

“Why does one go on pilgrimage? To get there, to be sure, but it is as much about the getting there as the there. One leaves behind home and creature comforts and picks up a backpack, seeking a particular place in which to leave behind other burdens – intangible burdens, yes, but heavy and cumbersome nonetheless. People go on pilgrimage to simplify, to unload, to pare down – material goods, yes, because whatever they carry they carry on their own backs, but also to simplify the contents of their own heads, to unload emotional baggage and pare down the noise of everyday living. They go on pilgrimage to create a space in time and place and spirit where they can put down their burdens and make room for better thoughts and ways of being. ”

Emily and I are both pilgrims. We’ve been on pilgrimage to Taizé, Glastonbury, Chimayo, Iona, the Holy Land, Assisi and Canterbury. In 2009, we walked El Camino de Santiago, the most profound and challenging pilgrimage of our lives.

For the last nine months, we’ve been on yet another pilgrimage. We’ve adopted some basic principles for our journey into this strange land of dementia.

Go where you’re invited and do what you’re asked to do.

Wherever you stand, be the soul of that place (Rumi).

Hold hands, especially when crossing a busy street or walking into a crowded room.

Don’t be embarrassed, afraid or too proud to ask for help.

When life gets overwhelming, walk in a park.

Make lemonade out of lemons, and then drink it.

Over the summer, we learned how to live with dementia and find meaning in it. During the fall, we traveled to Europe, where I preached and taught; and over the winter, we did the same on this side of the pond.

In February, our pilgrimage with dementia was interrupted by a night dream. In my sleep, I received a visit from my oldest friend in the world who is a doctor in California. During this dream, he said he had something important to share with me. I contacted him the next morning and arranged to visit him. He asked me in advance of our meeting to read an article about an alternative perspective on the treatment of dementia.

We met for dinner and then again for breakfast. Over morning eggs, he said, you don’t have to give in to dementia. You can slow it down and maybe even reverse it. But it will take some work. Are you willing?

I tentatively accepted his invitation, and thus began yet another three-month segment of our pilgrimage that involved spending Holy Week and Easter in California. Since people always ask for specifics, I’ll share some of my new “treatment.” We eliminated wheat from our diet and are trying to eat organic and on the low glycemic scale. I’m fasting for 12-14 hours a day, taking a few doctor-prescribed supplements, drinking lots more water, and being very intentional about meditation, yoga and exercise. We are improving our sleep hygiene: getting a king-sized bed, installing blackout shades, and trying to not use electronics right before going to sleep (not easy). I have done some metal and chemical detox, and I’m having regular craniosacral therapy.

I’m learning how to avoid busy intersections and crowded parties, and how to ask for help at the airport. Through speech therapy, spell check and Google, I am learning how to do work arounds when I can’t find words or make sentences. I’m also discovering how to use technology to compensate for my lack of executive function. Through physical therapy, I’ve learned how to recover when I start to fall, and how to walk with my head up high. I’ve organized my closet and minimized my wardrobe so that I don’t get overwhelmed in selecting outfits. I look at menus in advance of arriving at the restaurant so I can slowly decide what to eat. I’ve limited my daily activities and conversations so I don’t get too tired or run out of language. I try to avoid noisy bars and restaurants, sit with my back to the screens, and sometimes ask that the screen nearest me be turned off. I’m also learning to pay attention to my breathe when I get startled, overwhelmed, frustrated, frightened, or angry.

So, how am I doing? Well, I’ve lost 12 pounds; my blood pressure is at an all-time low; my knees don’t hurt so much; my muscle stiffness and spasms are under control; my head feels clearer; I have more energy; I’m not falling when I trip; and I’m not stuttering as much. But I still struggle with conversation and executive function, can’t recall names or recognize faces, and run out of language at the end of the day. I still can’t handle big crowds, coffee hours, or loud parties. I get anxious while driving in congestion; find reading difficult; and shuffle when I’m tired. I struggle to have deep, meaningful conversations — something I miss more than anything. I sometimes get confused when dressing in the morning, and I get panicked and frustrated when trying to move too quickly. I can’t manage more than one thing at a time and don’t like my routine interrupted. And yes, I have embarrassing outbursts and meltdowns, both in public and in private; fortunately, I don’t usually remember them when they are over.

The big difference is this: While we acknowledge that I have dementia, Emily and I no longer consider it a terminal disease with a countdown clock. We now think of it as a chronic illness that we can and will manage to the best of our ability for as long as we are able. Moreover, we are determined to craft a rich and full life with it — all the way to the end.

So after two years on this pilgrimage, we’re doing pretty darn good. Even though I’m trying my best to live in the present, I am interested in what will happen in the next three-month segment. Stay tuned for an update. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy some of my favorite photographs from our 2009 walking pilgrimage on El Camino de Santiago.

For the Love of the Lake

Emily and I live on Lake Erie, one of the Great Lakes that accounts for one-fifth of the world’s fresh water. For those of you who like facts: The lake’s name was derived from erielhonan, the Iroquoian word for "long tail," which describes its shape. It is the fourth largest of the Great Lakes when measured in surface area (9,910 square miles) and the smallest by water volume (116 cubic miles). As as a sailor, I describe Lake Erie as a big bathtub with fiercely rocking waves, often blustery winds, frustratingly dead calms, and unpredictable storms.

For a number of years, our backyard literally sat on the edge of the lake in the middle of a neighborhood just fifteen minutes from downtown Cleveland. Because Lake Erie forms our nation’s Northcoast with international waters bordering Canada, when we bought our lakefront property, we had to sign an agreement with Homeland Security that we wouldn’t harbor terrorists.

For nearly a decade, we were rocked to sleep by the sound of waves crashing against the rocks, and every morning we awoke to the noisy squawking and singing of birds of all species as they made their semi-annual migrations.

Our yard was a different climate zone from the rest of the metropolitan area. Tempered by the lake, summer days were cool so that we had roses until Christmas; the northern winds howled from late November through early to mid April; the snow blew over our house until the lake froze; there was lots of light - even on a cloudy, grey day; and in the spring, our bulbs popped up two weeks late. Most evenings, there were beautiful sunsets and amazing stars. And we had an extraordinary collection of wildlife, including: deer, possums, raccoons, skunks, woodchucks, and our very own coyote. We came to think of Lake Erie as both a moody but precious member of our household and a fascinating neighbor.

A few years ago, we downsized and moved into a neighborhood closer to downtown. Still wanting to live on the lake, we bought a parcel of vacant land and built an energy efficient house on a little street overlooking this vast body of water. Actually, it looks out over the Detroit Shoreway (now called Edgewater Parkway), the old mouth of the Cuyahoga River, Whiskey Island, and then Lake Erie.

In addition to migrating birds, we now see freighters unloading mounds of iron ore and uploading tons of salt. We watch trains, planes, and automobiles moving across our metropolis, consuming voluminous amounts of fossil fuel. Some of them carry highly combustible crude oil, and thus, are called “bomb trains.” We have an unobstructed view of Cleveland’s water intake facility (affectionately known as the Crib) and our water treatment plant, whose fragrance usually flows to the east of our house. We also have a new bike path behind our property whose construction unfortunately destroyed the natural habitat of our hillside, and has created so much light pollution that the birds are confused and we can’t sleep. Nonetheless, we still enjoy mother nature’s howling winds in the winter and her gentle breezes in the summer, and that beautiful and ever-changing view of water and sky for as far as the eye can see.

This morning, as I carried the kitchen garbage to our backyard compost bin and refilled the bird feeders, I paused to listen to the birds, smell the new spring flowers, watch the squirrels, admire the spiders, touch the one remaining old tree by the bike path, look up at the sky, and greet the lake. In doing so, I recalled the wisdom of Teilhard de Chardin: “The future of the earth is in our hands. Let us then, for the love of our Creator and of the universe, throw ourselves fearlessly into the crucible of the world of tomorrow…The task before us now, if we would not perish, is to build the earth.”

Living on the lake has made me appreciate the vulnerability of our ecosystem and its climate. But sometimes, I forget and take it for granted. In honor of Earth Day, I have recommitted myself to loving deeply from my heart and with my actions “this fragile earth, our island home.” I hope you will do the same. - Tracey