Life Happens in the Interruptions

Bacardi

Excerpts from a sermon preached on July 1

Chapel of St. James the Fisherman, Wellfleet, MA

As I stood in the pulpit, a scruffy man walked up the center aisle. Who was he, what did he want, and why was he interrupting my Easter sermon?

He stood in front of the altar, looked up at me and said, “Hey Mama, what’s happening?” With a smile of recognition and relief, I replied, “Good morning Pop. It’s Easter, and I’m talking about Jesus. So have a seat.” Sensing the congregation’s curiosity, I introduced my friend Bacardi. Spontaneous applause greeted him as he took a seat in the front row.

I met Bacardi on my first Sunday as rector of that inner city church. Finding myself in unfamiliar territory, I couldn’t help but notice a noisy group of men sitting on the litter strewn corner - drinking, laughing, and gesturing at me. Feeling both curious and out-of-place in my new suit and neatly pressed clergy shirt, I walked into a bodega and bought a few cups of coffee and a pack of cigarettes. I went back out on the corner and approached the men, offering each of them a smoke and some coffee.

“Who are you?” they asked. “I’m the pastor of the church,” I responded. They laughed, and one said loudly, “A woman preacher in that church, no way.” But we kept talking, and I invited them to come and see for themselves.

Over the years, Bacardi and his friends hung around my church, watching over its buildings and its female pastor. Sometimes, one or more of them would come in for food, clothing or shelter; periodically, one would seek my counsel or ask for money; and once in a while, they’d wander into the sanctuary to pray or make a confession.

So whether or not the Sunday congregation knew it, it made perfect sense that, in spite of his dirty clothes, scruffy beard and hangover, Bacardi came to church on Easter morning. What I didn’t quite understand was his unusual entrance.

In silence, Bacardi sat through the sermon, stayed for the prayers, and passed the peace. In silence, he listened to the choir anthem, witnessed the communion table being set, and watched the ushers bring up the offering. All’s well that ends well, I thought.

However, just as I was about to begin the Eucharistic prayer, Bacardi stood up. He walked to the altar, smiled at me, put a dollar on the Lord’s Table, wished me Happy Easter, and then left, this time by the side door. As he departed, I sensed a silent relief from the congregation, but I felt like It was a very holy moment. In an Easter morning interruption, the Risen Christ, disguised as a homeless drunk, had come among us and blessed us.

That’s how it is. Life happens, God acts, and Christ appears in the interruptions. Yet, we often experience interruptions as nuisances: a needy child intrudes into your conversation; an unexpected visitor disrupts your morning schedule; a cell phone rings during a concert; bad weather ruins your vacation; an emergency disrupts your weekend; or an illness, accident or death of a spouse interrupts your life.

Interruptions break into the normal state of affairs and stop the continuity of events. It is no wonder we’re taught as youngsters that it is not polite to interrupt others.

Though I don’t always welcome them in the moment, I have come to see interruptions as opportunities of divine grace waiting to be recognized and received. In fact, I believe that the Risen Christ is always standing in the shadows of life, and every now and again, more often than not, makes God known to us through some action or event, an interruption into the ordinary realm of possibility. We never know when Christ is going to move from the shadows to center stage. It just happens, and when it does, the normalcy and complacency of our lives is interrupted.

The evangelist Mark tells us that, “Wherever he went, into villages or cities or farms, they laid the sick in the marketplaces, and begged him that he might touch even the fringe of his cloak.” (Mark 6.56). Did Jesus reject or refuse all these interruptions? No, Jesus saw the realm of God at hand as an interruption to be welcomed.

On this Independence Day, our nation is being interrupted by the moral crisis of our current immigration policies. If you found yourself in one of the more than 600 locations participating around the country Saturday, you would have been interrupted by neighbors expressing disapproval of our government’s policy of building border walls, separating families, raiding workplaces, refusing visas, and keeping innocent people locked up in horrid detention facilities.

Families Belong Together Rally in Wellfleet, MA

What would Jesus do, and what is he calling us to do? I believe Jesus would not have passed by and ignored this crisis. He would have allowed himself to be interrupted, offered compassion to the suffering, and interrupted the political establishment by speaking out and expressing his opinion. You and I are called to do the same.

As Paul wrote, “I do not mean that there should be relief for others and pressure on you, but it is a question of a fair balance between your present abundance and their need, so that their abundance may be for your need, in order that there may be a fair balance.” (2 Cor 8:14)

Again, most of us don’t like to be interrupted, and we’re taught that it’s not polite to interrupt others. One of the challenges of gospel living is to make room for interruptions: to look up and stop what we’re doing when we hear, “Excuse me, I don’t mean to interrupt but….” God only knows what will happen, what gifts might be given and received, how we might be instruments of God’s grace, how we might ease someone’s pain or share in another's joy, and how we might experience the life of God more fully.

The other challenge of gospel living is to be willing to interrupt: to interrupt our neighbor when we need help; to interrupt our neighbor on behalf of another who needs help; to interrupt the status quo when it needs arousing; and to interrupt acts of hatred, evil and oppression whenever and wherever they may be found - even in the highest office of the land. For in and through the interruptions, we experience and release the life-giving power of God.

Yes, it might not be polite to interrupt others, but whoever said that Christianity was polite. So the next time you are interrupted, or you want to interrupt somebody else, remember – Life happens, God acts, and Christ appears in the interruptions. - Tracey

Speaking Out

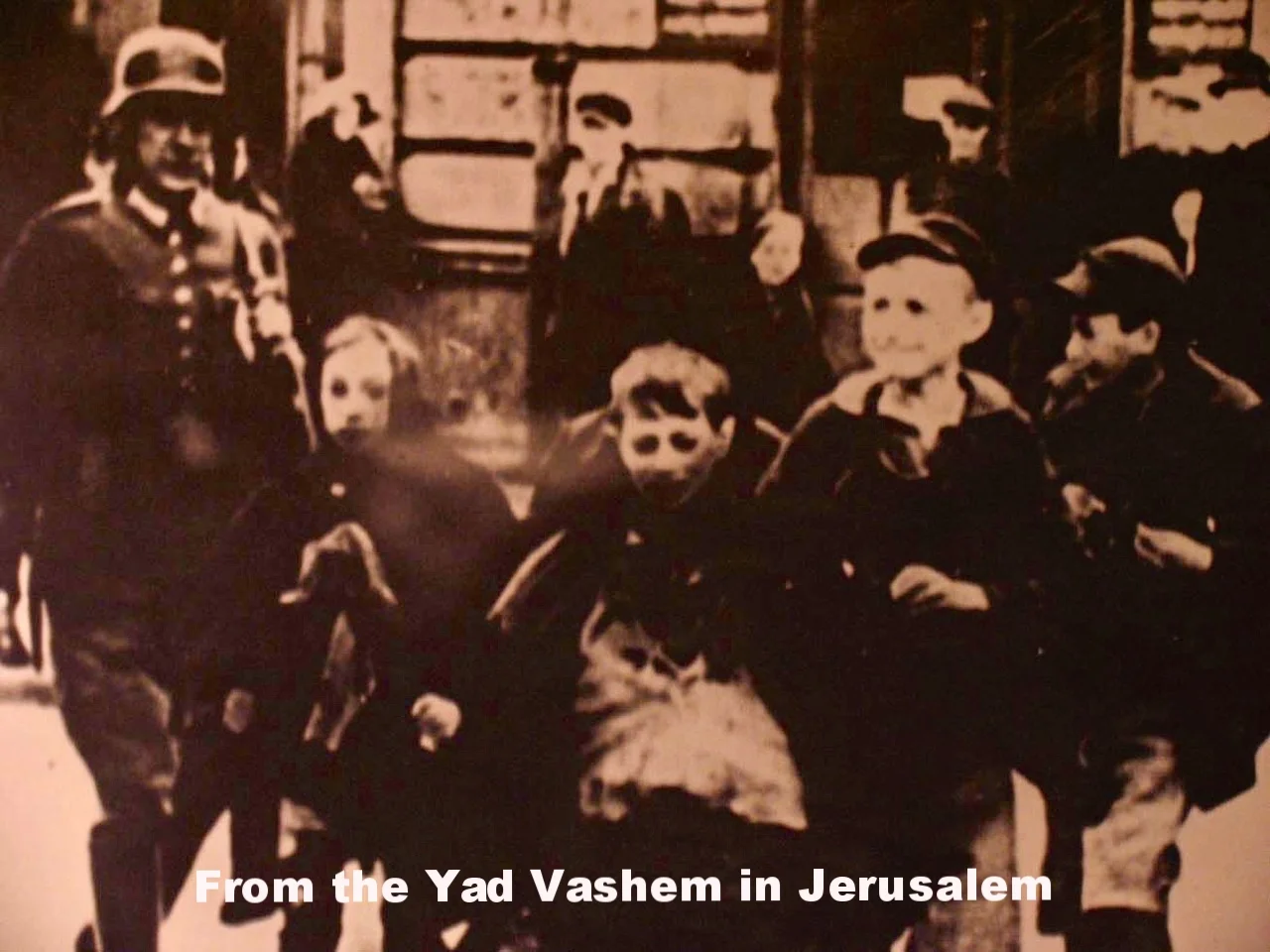

A half century ago, I sat in a classroom with a group of adolescents watching the film “Let My People Go,” a documentary about the Holocaust. I’ll always be haunted by the memory of emaciated corpses being pushed down a slide in the Warsaw Ghetto. At the end of the film, a young rabbi tried to elicit responses from a stunned and silent class of usually loud and obnoxious ninth-graders. I’ll never forget the moment when he looked at me, the only kid with a non-Jewish parent, and said, “Tracey, you don’t look Jewish. You could have passed. What would you have done?”

That accusatory statement, “You could have passed,” followed by the probing question, “What would you have done,” has haunted me all the days of my life. And just when I think I have put the accusation to rest and answered the question, it re-emerges as a beast from the deep recesses of my unconscious.

To pass has many implications. Passing can be as simple and as seemingly innocent as allowing a racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, or homophobic remark to go unnoticed. It can mean worshipping a homeless man on Sunday and walking by without seeing dozens of homeless men, women and children during the rest of the week. Passing can cause one to hide in all kinds of closets for all kinds of reasons. Passing can mean taking the easy way out, even at the cost of one’s soul. And now I’m learning that passing can simply mean doing and saying nothing as the world spins.

One of the common symptoms of FTD (Frontotemporal Degeneration) is inertia and apathy. These days, I lack the motivation, spontaneity and get-up-and-go energy that I used to exhibit, the kind of energy that community organizing and witness in the public square demand.

As I am unsure of my cognitive abilities, I’m afraid to speak out about what’s going on in our nation and world. I’m worried that I might say something inappropriate, not have my facts straight or be unable to handle the attacks that come from raising my voice.

And, since large crowds make me nervous, I tend to avoid public actions, marches and demonstrations. When it comes to standing up against the emerging policies and actions of our current presidential administration, legislature, and supreme court, especially on issues such as immigration, gun violence, the environment, healthcare, the economy, and foreign relations, I’ve taken a pass and become an armchair activist.

This past Sunday’s Hebrew Scripture passage tells us that, “God does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but God looks on the heart.”(1 Samuel 16:7). In the Gospel, Jesus compares God’s commonwealth to like a mustard seed (Mark 4:31), starting out as small and fragile but growing into a disruptive and disorderly weed that produces protective shade in which vulnerable birds and their precious cargo can safely nest.

Sitting on our front porch — where three different mother birds have nested in our hanging ferns — meditating on scripture, saying my prayers, reading newspapers, watching television talk shows, and scanning Facebook and Twitter — I realize that I can’t keep silent; I can’t take a pass. As we approach Independence Day, all of us need to speak out about the policies and actions of our nation’s government.

What’s happening in our country frightens me. As a student of history, I’m seeing too many comparisons with previous fascist regimes, especially the Roman Empire and the Third Reich. In my mind, the often repeated words of Martin Niemöller, inscribed on the wall of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in our nation’s capital, are taking on new and more urgent significance.

“First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Like many Protestant clergy in Germany, Niemöller was a conservative Lutheran pastor who initially supported Adolf Hitler’s ascent into political power. However, in 1934, coming to see the growing abuses and hatred perpetrated by the Third Reich, Niemöller joined with other Christian clergy to form the Confessing Church and to criticize Nazi policies and practices as incompatible with Christian values. Along with other resisters, Niemöller was arrested and sent to a concentration camp.

They are coming for black and brown people. They are coming for immigrant people. They are coming for queer people. They are coming for poor people. They are coming for sick people. They are coming for oppressed people, including the most vulnerable among us — undocumented migrant children.

Drawn by a Palestinian child

As a person with dementia, I am worried. I no longer qualify for certain kinds of insurance because I now have a pre-existing condition. What if our financial resources aren’t sufficient to provide for my care as my disease progresses? Will my spouse be forced to spend every last dime on my care, leaving herself impoverished; or, will I eventually be perceived as a burden on society and warehoused in some government facility? Even if I can afford quality care, will my advance directives be honored and my end-of-life decisions be respected by a government whose policies and judicial decisions are becoming more rigid and less compassionate? Will they come for me, and there will be no one left to speak up?

In 1973, William Stringfellow, lawyer, political activist, and devoted Episcopalian, published an essay entitled “Living Humanly in the Midst of Death” in the book An Ethic for Christians & Other Aliens in a Strange Land. Examining why people like Niemöller spoke out in resistance to the Third Reich, Stringfellow wrote, “To exist under Nazism in silence, conformity, fear, acquiescence [and] collaboration – to covet ‘safety’ or ‘security’ on the conditions prescribed by the state – caused moral insanity, meant suicide, was fatally dehumanizing, [and] constituted a form of death. Resistance was the only stance worthy of a human being, as much in responsibility to oneself as to all other humans, as the famous commandment mentions.”

Stringfellow argued that while resisting oppression ensured risk and peril, nonresistance or acquiescence “involved the certitude of death – of moral death, of the death to one’s humanity, of the death to sanity and conscience, of the death that possesses humans profoundly ungrateful for their own lives and for the lives of others…”

I think we would be well advised to heed the words of both Stringfellow and Niemöller, and speak out while we still have the freedom to do so. Otherwise, as hard as it is to imagine, there might come a time when exercising our freedom of speech might become a risky and dangerous act. And, if we are silent for too long, there might not be anybody left to speak for you and me. - Tracey

________________________________________________________________________

“Living Humanly in the Midst of Death,” A Keeper of the Word: Selected Writings of William Stringfellow, edited by Bill Wylie Kellerman (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994) 345

Do Not Lose Heart

Excerpts from a sermon preached on June 10

Trinity Church Wall Street, New York City

Do you ever feel discouraged and wonder if all the effort is worthwhile? Are you ever tempted to give up and retreat into yourself? If so, you’re not alone. It happens to everybody, and it’s a particular temptation in these times that try our weary souls.

Over the past two decades, thanks to the internet and the 24-hour news cycle, we have witnessed tragedy, violence, deceit and disappointment over and over again, making it tempting for many of us to throw in the towel and pull a blanket over our heads. In fact, cocooning - retreating from the world - is a growing consumer and lifestyle trend.

The temptation to “lose heart” is as old as history itself. Paul writes to the Church in Corinth: “We do not lose heart;” (NRSV) “We’re not giving up;” (The Message); “We will never collapse;” (Phillips) or in the words of the Common English Bible, “We’re not depressed…[For] even though outwardly we are wasting away, inwardly we are being renewed day by day.” (Taussig).

The “outer nature” of which Paul speaks is the daily grind that includes pain, suffering, betrayal, loss and defeat. Our “inner nature” is the not-yet-perfect or complete life that emerges, evolves and matures through our relationship with God. Thus, Paul contrasts our “outer nature” as a tent compared with our “inner nature” as a house or building “not made with [human] hands,” but permanent and eternal.

Having read this passage at dozens of funerals, Paul’s words now hit home for me in a new way. For the past two years, I’ve been trying not to lose heart, get depressed, collapse, or give up as my outer nature - that is, my brain - is wasting away, literally shrinking due to early onset dementia. What gives me heart - in other words, hope and encouragement - is that my inner and spiritual nature, the person I am on the inside, is being renewed, restored, refreshed and recreated by God each and every day.

While my earthly tent is slowly degenerating, and things on the outside might look as if they are falling apart, my home in God’s realm - even here on earth - is becoming a really beautiful mansion, and “not a day goes by without God’s unfolding grace.” (The Message).

Sure there are challenges as I struggle with aspects of life that I used to take for granted. While I get tentative and anxious, afraid that I will forget something important, not recognize someone I know, or that I will become overwhelmed by my environment, at this stage of my disease, I’m also experiencing life in some new and wonderful ways, and I’m beginning to think that dementia has provided me with a short-cut to the realm of God.

The great wisdom teachers, including Jesus and his apostle Paul, speak of dying to oneself and being reborn, or losing life and finding it anew. Richard Rohr calls this process “falling upward” into the second half of life, discovering what might be described as the fullness of life.

The first half of life is about building a container called identity and filling it with family, friends, education, career, hobbies and stuff. We also fill our first half of life container with successes and failures, accomplishments and defeats.

The second half of life happens when the contents of our identity containers are spilled out and refined, and the container – worn, dirty, chipped and perhaps even broken and re-glued – is refilled. Now with all of its contraction and paradox, pain and joy, we hold our containers in what Rohr calls luminous gravitas, a bright sadness.

I realize that I’m falling upward – into the fullness of life – with dementia. I have no doubt that I am losing the life I’ve always known. I’m also certain that I’m finding a new one. We all stumble or fall into the second half of our lives through various ways: loss of a job or a spouse, illness, retirement, or that unexplainable midlife crisis.

Our hardships can be gifts in disguise, because they help us develop courage, resilience, love, compassion and faith, the cornerstones of a firm foundation. And, in the meantime, the in-between time, as we endure the demolition and new construction, wondering what the future holds, we have to believe that we are a work in progress.

All of us are given “opportunities to get close to life.” We just have to go along for the ride. Annie Dillard was correct in her observation that, “We should all be wearing crash helmets.” For God is not finished with us. Our present situation is not our final destination. No matter what challenges life hands us, God is still building a great mansion, a home for all of creation, a body worthy of the divine residence. So don’t lose heart. Rather, enjoy living in a construction zone! - Tracey

Hearing the Voice Within

Life happens in the interruptions

Excerpts from a sermon preached on June 3

Christ Church Cathedral, Indianapolis

“Lord, you have searched us out and known us;

You know our sitting down and our rising up;

You discern our thoughts from afar.

You trace our journeys and our resting-places

and are acquainted with all our ways.

Indeed, there is not a word on our lips,

But you, O Lord, know it altogether. Amen.

”

God often interrupts our lives: calling us by name; communicating with us in words, actions, symbols and signs that we can understand; and inviting us to do extraordinary things like healing the wounded, raising the dead, and bringing joy to those who despair.

As a young adult, I had a passion for justice and wanted to be a preacher who would change the world, but as a child of an interfaith marriage, I just wasn’t sure whether I should become a rabbi or a minister. Eventually, my quest led me to the Union Theological Seminary in New York City, right across the street from the Jewish Theological Seminary. My first semester was a prolonged interrogation of God. Who are you? Do you really exist? What’s your relationship to Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, and all the rest? Is the Bible really your word? Is it true? Why are so many bad things done in your name? You know those questions. You’ve probably asked some of them yourself.

I was also trying to sort out my life, and I wasn’t clear about what would become of me. By January, I was utterly exhausted from taking on someone bigger and stronger than me. I found myself walking down 42nd Street one day asking God to just let me go and get on with my life. And then it happened.

As I was crossing Madison Avenue, a voice called out from within me saying, “I’m not going to let go of you.” Ignoring the voice, I kept walking and went about my business. An hour later, walking out of a building, it was as if the voice was leaning against the door waiting for me. “Why me?” I asked, and the voice replied, “Why not?” “What do you want with me?” I inquired. “Your life,” the voice responded.

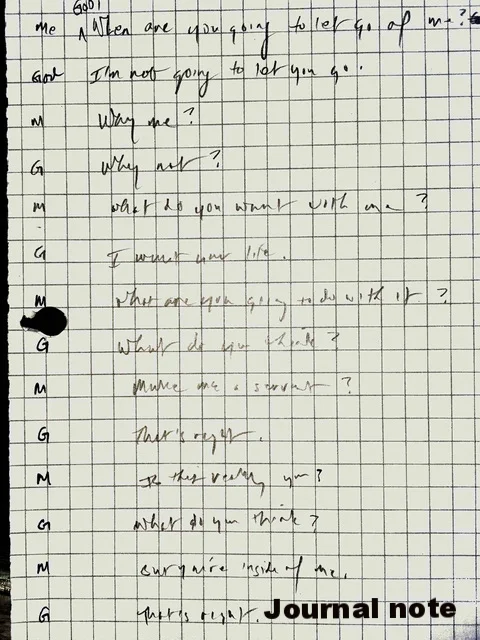

At that moment, I realized something was going on to which I had better pay attention. I looked up and there was a McDonald’s. I walked in, ordered my usual cheeseburger-fries-and-coke, sat down at a table, and starting writing out the most remarkable and memorable conversation I’ve ever had with anyone. Scribbling as fast as I could, I wrote T for Tracey and G for the voice.

Mixed blessings

While my conversation at McDonald’s was very personal, I am convinced that the voice I heard is also the voice that Samuel heard. It is the voice that Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Job, Mary, Jesus, and Paul all heard. I believe that this voice - this divine presence - resides in each and every one of you as well (albeit speaking in different languages and appearing in different ways that each of us might understand). If everyone would hear and follow it, our individual lives would be enriched, our imaginations would be set free, creativity would flourish, and this fragile and endangered world would be a better (and I think, safer) place to live.

So you might be wondering, how does one hear this voice? Try following the advice that old Eli gave to young Samuel: be quiet, wait, listen, and receive.

Eli instructed Samuel to lie down, and when he heard his name called, he was to invite the voice to speak. So Samuel did just that, and God spoke. You might never hear what God has to say if you don’t (in your heart and mind, as well as your ears) invite God to speak.

Once you ask a question, or extend an invitation, you have to wait for a response. God immediately spoke to Samuel, but it doesn’t always happen that way. Patience is required. God might take a little time in accepting your invitation, and God’s response might come in unexpected ways: through a conversation, a dream, a sign, a vision, or even silence. It took awhile for God to speak to Job, and then the voice came from out of a whirlwind. It took years for God to respond to my persistent pleading. God also might manifest the Divine Self in unexpected times and places – on top of a mountain, in the belly of a whale, under a fig tree, or even at a McDonald’s.

To hear God’s voice, we have to develop a habit of listening. The Zen masters call it mindfulness, contemplatives call it meditation, and mystics speak of it as contemplation. Whatever one calls it, you can’t hear the voice without listening, and that might mean silencing all those other media filling up our airwaves. Moses climbed a mountain, Eli instructed Samuel to lie down; and Paul was brought to his knees by a lightning rod.

The day after my McDonald’s conversation, one of my professors said that faith is a two-way street: it’s a gift and a willingness to receive the gift. The voice and wisdom of God is a gift that can only be actualized by receptivity. Abraham had to believe the promise of land and descendants, Moses had to accept the call of leadership, Mary had to welcome an unplanned pregnancy, and Thomas had to touch Jesus’ wounds. Remembering the example of Jesus in the wilderness, it’s also a gift that must be tested to ensure it’s calling one to build up and not destroy, to love and not hate, to do good and resist evil, and to respect the dignity of every human being and the rest of creation.

Most, if not all of us, are perplexed by life, but we don’t have to be driven to despair. We all get struck down, but we don’t have to be destroyed. And, whether we can preach like Peter, pray like Paul, prophesy like Eli, or lead like Samuel, we can all hear the voice of God in our lives and carry God’s wisdom into the world. Really, all you have to do is be quiet, wait, listen, receive, and then respond in faith, hope and love. - Tracey

Good Things Come in Threes

For most of my parochial ministry, I struggled with the doctrine of the Trinity. For those of you who aren’t religious but remember Don McLean’s song, “American Pie,” it’s the phrase embedded in the lyric line, “The three men I admire most, the father, son and the Holy Ghost…”

The traditional words of the Trinity are simply not adequate to express my understanding of the divine. While I know them by heart, I can say them by rote, and sometimes, they offer a poetic sense of the familiar. God has to be more than in the words of an old friend, “two men and a bird.”

According to legend, St. Augustine learned from a little boy that trying to comprehend the Trinity is like trying to fill a hole in the sand with water. It’s pointless. So every year, when Trinity Sunday rolled around, I’d spend hours figuring out how, in a meaningful way, to talk about something that I never really understood and not even sure I believed in the traditional, doctrinal formula. However, through the lense of dementia, I am acquiring a new appreciation for the mystical number three.

I have Primary Progressive Aphasia – that is, the loss of language. It’s getting harder for me to speak and write, especially in the evening, in busy environments, in conversation with more than one person, and when I’m feeling pressured. Contrary to my extroverted nature, I now can spend entire days without talking, and I’m becoming increasingly reliant on Emily to speak on my behalf, and on others to keep up the conversation.

Just this morning, I had a very difficult time asking for assistance at Home Depot. I couldn’t remember the word for the product I needed; I couldn’t think of appropriately descriptive words; I was stuttering and using my hands to try and explain myself; and I could see the salesman’s patience wearing out. Eventually, I had to say, “Please forgive me. I have problems with language. I’m having a hard time telling you what I need.” He smiled, slowed down, reassured me, and helped me find what I wanted, carefully placing the items in my basket and instructing me that they could always be returned. I was grateful but somewhat humiliated.

On the other hand, once I figure out what I want to communicate and – with the help of Google's dictionary, thesaurus, and spell-check – write it down, I can deliver my message with relative ease and confidence. As Emily likes to say, one day I can preach a kick-ass sermon, and the next day I can’t put two sentences together. However, it does take a long time (and it feels like eternity) to get the words out of my head and into the world.

A child psychologist explained to me, making language is a three-step process to which we don’t usually give much thought. First, we have to decide what we want to communicate; second, we must recall how to say or write it; and third, we have to do it. Most of us take the art and action of language for granted. But when you’re struggling to think, speak and write, it is exhausting. By the time I get to the third step, I often want to give up, or the conversation has moved on. Sometimes, sitting around a dinner table, I feel like I’m in that E.F. Hutton commercial where everybody leans in to hear what brilliant wisdom I have to say, and then they patiently wait for me to get a mundane sentence out of my mouth.

I’m coming to realize that, with the exception of involuntary actions like breathing, nearly everything we do in life is a three-step dance: we have to decide what to do, how to do it, and then do it. For most adults, this comes so naturally that we deceive ourselves into believing that we can do several things at once, like drive, listen to the radio, admire the view, talk on the phone, and follow directions. I used to do all of that while eating a sandwich and driving over the speed limit in rush hour traffic on the New Jersey Turnpike. However, brain scientists will tell you there really is no such thing as multitasking. We just do a lot of stuff really fast.

People living with dementia can only do one thing at a time, and that becomes increasingly difficult as we desperately try to recall and execute the steps of the dance with as much grace as possible. These days, I often begin to speak a thought and then give up and say, “Never mind.” Or I start a project, like cooking, organizing, ordering, or fixing something, get confused and frustrated, and just walk away. They tell me that at the end-stage of this disease, I probably won’t be able to walk, speak or even swallow. I don’t like to think about that.

So here’s a piece of advice: When you’re dealing with someone who has dementia, especially someone who struggles with aphasia and executive function (that is, planning, organizing, and executing), consider it an exercise in patience. Allow us the time to speak and act; help us if we’re clearly struggling; recognize that we might have to outline what we’re going to say and do before we say and do it; and realize that we might not make it through all three steps of the dance.

Now, back to the Trinity. I still can’t explain it, but since this past week we celebrated Trinity Sunday, I want to share with you words that I hope I will never forget – words that I heard one day when God first interrupted my life. A voice said, “I was Jesus on earth, but I’m still God, and I’m here with you now.”

As I think back on my conversation at McDonald’s, I realize that like St. Augustine, I reached the limits of my understanding of the Holy Trinity’s mystery. I did come to believe that it was God’s voice of love I heard. The voice was love; it came to love, and it teaches us how to love.

John Lennon once said, “All you need is love, love, love.” At the royal wedding, Bishop Michael Curry preached that the power of love can and does change the world. As I grow older, The Voice I heard on 42nd Street has become for me a Trinity of Love: love unbegotten, love incarnate, and love among us now.

The Trinity of Love is my way of understanding the mystery we call God, and I don’t need to comprehend or explain its meaning any further. I just need to return that love to God and my neighbor with all my heart, and soul and might. And, I have to remember to love myself, especially when I get tangled up in the increasingly complicated three-step dance of making language and managing the trinity of life with dementia. Make of it what you will – good things do come in threes.